Having assigned the task of reducing 1974 to twenty albums, it soon became apparent that at least to my b. 1980 ears, it was as great a year for African albums as it was a mediocre one for the Anglosphere. Was it the greatest year for African albums? Who knows, not me, but it seems plausible. Ten for Africa and ten for the rest of the world felt like a fair split. If anything, this turned out be harsh on Africa: I’d play the last one out here, Celestine Ukwu’s Ilo Abu Chi, over Radio City four days a week. The continental top ten I settled on contains four entries from South Africa, two from then-Zaire, two from Nigeria, and one each from Ethiopia and Guinea; take this as an approximation the state of my knowledge (and the state of English-language knowledge of classic Afropop) rather than a declaration of All That Was True and Good about African music that year. Some are compilations of previously released singles; who cares. I absolutely don’t guarantee that all dates are 100% correct. The list is slightly in order: faves tend to be near the top, but I wouldn’t wager the CD of Omona Wapi I finally acquired on any exact ranking.

Franco & l’Orchestre TP OK Jazz: Untitled (Mabele (Ntotu))

Franco & l’Orchestre TP OK Jazz: Untitled (AZDA)

The compilation that’s called 1972/1973/1974 on streaming services consists of slightly edited versions of two albums originally released in 1974. Each album is either untitled or known by the generic title Editions Populaires (the label name), so that doesn’t help. Tracks 1–5 (starting with “AZDA”) make up the one with the orange-faced cover, while tracks 6–12 (starting with “Mabele (Ntotu)”) make up the one with the green-faced cover, except in some images it looks like the colors are reversed. The complete version of the second album, with a few extra minutes of extended cuts, is on Spotify as Mabele (Ntotu) in marginally worse sound quality. However you choose to listen to them, this is, in my opinion, the best band in the world at the time—maybe for the first time, with Ellington passing and the James Brown organization’s accounting deficiencies finally starting to take their toll. “AZDA”, which somebody around here called his favorite African song of the Seventies, is the most well-known track in the West—I think it’s not quite as beloved in the Congo, probably because ten minutes of sponcon for a Volkswagen dealership is less spiritually uplifting if you’re fluent in Lingala—but Mabele might be the deeper collection. Its lead track has Simaro’s songwriting at its most poetic and a young Sama Mangwana showing he was already Franco’s most effective vocal foil. “Kinsiona” and “Mambu Ma Miondo” go to dark places rare in Franco’s oeuvre: the former is an unusually angry song of mourning (for his brother), the latter a tribute to the assassinated Amílcar Cabral and the anti-colonial struggle more generally. Everywhere there’s the guitar sound a whole continent tried to rip off.

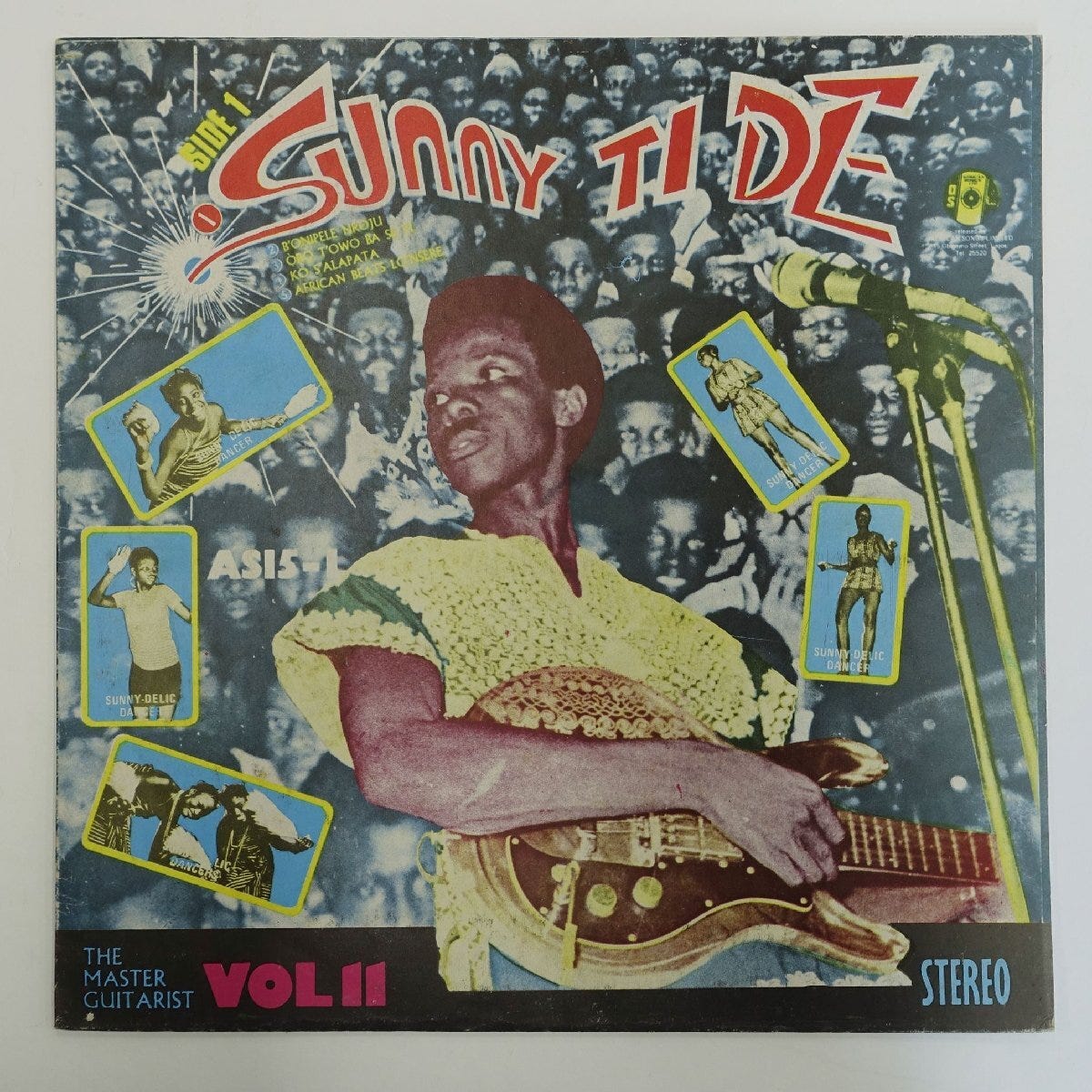

Sunny Adé & His African Beats: The Master Guitarist Vol. 11: Sunny Ti De

On YouTube in two parts. Each side nominally consists of five tracks but is a continuous piece of music, Side A you may remember as the opening of the 2003 comp The Best of the Classic Years and it might actually be the best of.the classic years: whoever the talking drum player is is in rare form. The “Oro T’onlo” medley that makes up Side B is about 80% as good. Once you’re done with this, there’s Syncro System Movement, which is quite different again. These were the last two entries in African Songs Ltd.’s The Master Guitarist series; Adé then moved to his own label and released Sunny Ade, Vol. 1, a solid-not-great album that was just the start of confusion among discographers.

Batsumi

Possibly the best South African jazz album, and very likely the best one not made by Norwegians (is what I’d say if I were trying to get in trouble.) Sax player Themba Koyana has a particularly fine tone and Thabang Masemola has the only jazz flute ever to have some grit in it. Vocals in four languages that firmly but methodically undermine Apartheid create a sense of identity that Scandinavians can’t recreate. And when the pianist breaks into “Für Elise”, it shows love and theft go both ways.

Umculo Kawupheli / Soweto Never Sleeps / Duck Food

Seven songs from the Mahotella Queens (three of them “oh that one” classics), two each from the Mgababa Queens and the Dark City Sisters, one from the little-known Irene Ngwenya and her Sweet Melodians. There’s Marks Mankwane on guitar in front of the world’s greatest rhythm section at the time (possibly excluding Jamaica.) There are ersatz Mahlathinis who try their best. And in addition to the uniformly excellent singing, there’s a sense of South African women speaking for themselves a bit louder.

Fela Kuti & the Africa 70: Confusion

Standards were such that Fela might’ve been the third-best bandleader in Africa, and in the world, at the time. The famous five-minute drums-and-keyb into is just the start of Tony Allen’s greatest performance, while Fela’s pleasantly noodly. The rest of the song, when it arrives, is fine enough, with Tony Njoku’s trumpet particularly on point. And if a twenty-five minute song sounds too long, listen to Alagbon Close, Fela’s other ’74 album, and try not to think it should’ve been all A-side.

Indoda Mahlathini: Ngibuzindlela

Jumping from Gallo over money, Mahlathini assembled a new set of Queens easily enough, led by Joyce Makhanya, who could help out by writing party songs and paeans to Indoda (“The Man”) Mahlathini. Lazarus Magatole also contributes to writing as well as supplying higher-voiced groans that make for just as effective a contrast to the Man as the Queens do. All that’s missing is the world’s greatest rhythm section. (Most of this is on the 1987 compilation The Lion of Soweto.)

Mulatu Astatke: የካተት (Ethio Jazz)

This is also available as tracks 1 and 7–14 of Ethiopiques 4 in a different order. Ethiopia has always been among the hardest African scenes for me to grasp, so I don’t guarantee this is actually better than, say, the Mahmoud Ahmed self-titled that Frank Kogan voted for. All I can say is the off-kilter feeling that Ethiopian music often induces in Western listeners is present but in check here, and the pentatonics are in no way a constraint on the freedom that Astatke’s piano and Fekade Amde Maskal’s sax achieve.

Bembeya Jazz National: Special Recueil-Souvenir Du Bembeya Jazz National (Mémoire De Aboubacar Demba Camara)

Demba Camara, singer and bandleader of Guinea’s national orchestra, died in a car crash in ’73; state record label Syliphone compiled this as a tribute. Guitarist Sékou “Diamond Fingers” Diabaté stands out by being perhaps the first to blend the standard post-Docteur Nico African guitar style with griot ideas first developed on instruments like the kora. The songs allegedly (out of necessity) praise strongman Sékou Touré more than one might like, but fortunately I haven’t found translations. There are multiple versions of the album and I’m not sure which is the original, but the reissue Hommage à Demba Camara, has decent sound and fun bonuses (including a Louis Armstrong impersonation, why not.)

Abdullah Ibrahim Orchestra: African Space Program

Super busy year for Ibrahim, with nine albums I identified if you include his work with Don Cherry. This is the best of what I managed to hear, with Ibrahim leading a twelve-piece band (including nine horns) and at least matching Sun Ra, keeping them all in strict unison until it’s time for them to explode into the vacuum, and of course that just makes the melody blasts all the more joyful when they return. You might find The Third World’s Underground, with Cherry and Carlos Ward, similarly impressive if you like free improv and don’t automatically say “but where are the drums”. Then there’s “Mannenberg”, a much more traditional work of Cape jazz to the point of near-cheesiness, but it became one of the key anti-Apartheid themes of ’70s so who cares?

Honorable mentions

Celestine Ukwu released a couple of albums in 1974, the better known of which is Ilo Abu Chi. That one doesn’t match True Philosophy (aka the one with “Igede”), which was probably the best African album of 1971, but holds up by any other standard. (Three of its tracks were compiled on No Condition Is Permanent.)

I would need to know much more about Sufi music to accurately rate Master Musicians of Jajouka (aka The Primal Energy That Is the Music and Ritual of Jajouka, Morocco, aka the one with the song “Brian Jones” but not the one produced by Brian Jones.) Recorded before the group’s feuds and splinterings, it’s said to be their least Westernized album, and it does get nicely trancey without turning into psych-mush.

Manu Dibango’s Super Kumba is by no means a deep groove album, but he’s always a fun soloist to listen to and it’s amusing to hear disco emerging out of funk in multiple parts of the world simultaneously.

Subjects for further research

North African discographies, or at least what I find in English, are a mess even compared to the rest of the continent. Sources say modern raï was under development by that point, but searching Discogs and Rate Your Music turned up zero albums (one suspects those sources do not include a complete record of EPs that Cheb Khaled recorded when he was fourteen.) And I don’t even know what I should be looking for re: Egypt.

Other stuff I know almost nothing about: Lusophone African music; non-South Africa Southern Africa besides the Hallelujah Chicken Run Band singles; whether anyone in Tanzania got around to making an album.

Your release date verification process is clearly at least better than mine, which short circuited completely as I combed through (not enough) African albums in my survey. So thank you!

Shave three or four minutes off the end of Confusion, put "Alagbon Close" on side two, and you have one superb album instead of one very good one and one pretty good one.