A beginner’s guide to Latin American poetry

Plus: Olivia Rodrigo, if you scroll down far enough

A reminder that my “beginner’s guides” are “guides by a beginner”. I don’t claim that my 2100 day Duolingo streak gives me nearly enough Spanish to understand the originals, so I mostly read bilingual editions—reading the Spanish out loud does help. I can’t even fake Portuguese so Brazilian poetry will have to be some other lifetime.

Eugenio Montejo (Venezuela, 1938–2008)

What I’ve read: The Trees: Selected Poems 1967–2004 (tr. Peter Boyle)

A straightforward entry point. The book is mostly short lyrics; the Spanish is pretty readable for an intermediate student. Montejo writes about the old school poetic staples (death, family, Iceland) in a way that for all its apparent ease doesn’t get overwrought or soggy. One of the few 20th century poets for whom “lovely” is the highest of compliments.

Top five poems:

Álbum de Familia/Family Album

Nana para Emilio/Lullaby for Emilio

Partitura de la Cigarras XV/The Cicada’s Score XV

La Estatua de Pessoa/The Statue of Pessoa

Amantes/Lovers

Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina, 1899–1986)

What I’ve read: Selected Poems (ed. Alexander Coleman)

Some of these are poetry poetry, some are shaggy miniature dogs. Borges is an easy sell because he has punchlines: if “Parable of the Palace” shares one with Tenacious D’s “Tribute”, you know he’s going to be meaner about it. And he can be shockingly lyrical too, though arch-conservative that he is, only about old stuff.

Parábola del palacio/Parable of the Palace (tr. Kenneth Krabbenhoft)

Alejandría, A.D. 641/Alexandria, A.D. 641 (tr. Stephen Kessler)

Museo/Museum (tr. Krabbenhoft)

A una espada en York minster/To a Sword at York Minster (tr. Charles Tomlinson)

El remordimiento/Remorse (tr. Willis Barnstone)

Pablo Neruda (Chile, 1903–1973)

What I’ve read: The Essential Neruda: Selected Poems (ed. Mark Eisner); The Heights of Macchu Picchu (tr. Nathaniel Tarn)

You can argue about whether he really was the LatAm poetry GOAT, but there’s no question he was The Guy. There’s great surrealism, political fire, pretty good old man poems when the time comes, and oh yeah, the creation of a Latin American artistic identity. The Tarn Heights of Macchu Picchu is the place to start; there’s much more I need to get to.

El fantasma del buque de carga/The Phantom of the Cargo Ship (tr. Stephen Kessler)

Explico algunas cosas/I Explain Some Things (tr. Eisner)

La poesia/Poetry (tr. Alastair Reid)

Alturas de Macchu Picchu/The Heights of Macchu Picchu (tr. Tarn)

Sí, camarada, es hora de jardín/Right, comrade, it’s the hour of the garden (tr. Forrest Gander)

César Vallejo (Peru, 1892–1938)

What I’ve read: The Black Heralds (tr. Rebecca Seiferle); The Complete Posthumous Poetry (tr. Clayton Eshleman & José Rubia Barcia)

People who are usually right about poetry say Vallejo is the greatest, and they’re probably right, but he is Difficult. The Black Heralds, the first of two poetry books he published during his lifetime, is probably the better place to start, as there at the least literal meanings are usually clear, though thinking about, say, what “the child-Jesus of your love” is “Christmas Eve” signifies could fill an essay. But the posthumous works, translated freely by Eshleman (“¡Me friegan los cóndores!” becomes “Fuck the condors!”), are deeper, even though I surely have errors in understanding not resolved by visiting his old house El Rincón de Vallejo in Trujillo, though at least I got to try cuy frito at the restaurant. Trilce is meant to be trickier still from the Google-translated-baffling title onwards, so give me a few years to psych myself up for that one.

Top five (all posthumous):

Telúrica y magnética/Telluric and magnetic

Himno a los Voluntarios de la República/Hymn to the Volunteers for the Republic

“Alfonso, estás mirándome, lo veo…”/“Alfonso: you keep looking at me, I see”

“¡Ande desnudo, en pelo…!”/“Let the millionaire go naked…”

Hallazgo de la vida/Discovery of life

José Lezama Lima (Cuba, 1910–1976)

What I’ve read: Selections (ed. Ernesto Livon-Grosman)

Best known for his novel Paradiso, Lezama Lima primarily considered himself a poet. Selections is English-only, but the poems therein have a slipperiness regardless of translator that’s in concord with his reputation. “Rhapsody for the Mule” is ostensibly about a mule that falls off a cliff, but does it ever hit the bottom, and where is God anyway? Lezama Lima offers plenty that seems tantalizingly graspable, which doesn’t mean you won’t go kersplat.

Rhapsody for the Mule (tr. G.J. Racz)

The Music Car (tr. Racz)

Dissonance (tr. Roberto Tejada)

Thoughts in Havana (James Irby)

The Adhering Substance (tr. Irby)

Octavio Paz (Mexico, 1914–1998)

What I’ve read: The Poems of Octavio Paz (tr. Eliot Weinberger)

If nothing else, the doorstop Weinberger will make you see why Bolaño had a love-hate (trending towards the latter) relationship with Paz. Rarely has someone tried to write like a Major Poet and pulled it off for at least a few decades. Long works like Sunstone and Blanco consciously announce themselves as the conjunction of Latin American and North American (post-)modernities, and he has the chops to get away with this at least through 1974’s A Draft of Shadows. It’s true that some of his earlier work, like the de Sade tribute/goof “The Prisoner”, is much more likable. But Major Poets don’t have to be likable.

El prisionero/The Prisoner

de Trabajos del poeta/from The Poet’s Work

Piedra de sol/Sunstone

Blanco

Rubén Darío (Nicaragua, 1867–1916)

What I’ve read: Selected Poems of Rubén Darío (tr. Alberto Acereda and Will Derusha)

He’s the fountainhead, so you should read him eventually, but perhaps don’t start with him—he’s very much a product of his time, full of references to minor mythological figures you need to be a classicist or at least French to appreciate. At his best, he has a hint of modernity that devours his florid side, like a hawk snapping up a dove. And he shows real fire when he’s proselytizing against the United States as the fake America, even if in later life he got really into eagles.

A Roosevelt/To Roosevelt

Anagke

Qué signo haces…?/What sign do you give…?

Nocturno/Nocturne

Era un aire suave…/It was a gentle air…

David Huerta (Mexico, 1949–2022)

What I’ve read: Before Saying Any of the Great Words (tr. Mark Schafer), various stuff in journals

Maybe the great political poet of his time, and almost certainly the greatest one read by more than three people in a Marxist book club (no offense Marxist book clubs.) A big chunk of Before Saying Any of the Great Words is a partial translation of Incurable (1987), and I really want a complete version—“Glass Door” seems like a tricky account of getting mauled by the riot cops, but it’s impossible to know all of what it means without the whole context. Huerta stayed righteous throughout his career: “Ayotzinapa” is about the arrest and presumed massacre of 43 teachers’ college students in 2014; this time, there’s no ambiguity about the author’s stance.

Antes de decir cualquiera de las grandes palabras/Before Saying Any of the Great Words

Luz de los mundos paralelos/Light from Parallel Worlds

“Twice I wished to fall, then I wished to fall nineteen times”

Ayotzinapa (tr. Mark Weiss, warning: image of a dismembered corpse at the link)

Coral Bracho (Mexico, b. 1951)

What I’ve read: Firefly Under the Tongue (tr. Forrest Gander)

Greatest living blah blah blah and someone who should be in Nobel contention, if only the Swedish Academy were good at poetry. The bilingual is very useful here, capturing the sensuality of Bracho’s language both in Spanish and in Gander’s translation. Lots of polysyllables and voiced consonant in the early work; when the language becomes simpler in later poems like “The Rooms Aren’t What They Appear to Be”, the mystery remains. There’s a newish book of Gander translations, It Must Be a Misunderstanding, that I really should get to.

Agua de bordes lúbricos/Water’s Lubricious Edges

Los murmullos/The Murmurs

Imagen al amanecer/Dawn Images

Ese espacio, ese jardín II/That Space, That Garden II

Subjects for further research

The pro-Vallejo vanguard usually says that Chile’s Vicente Huidobro is up there with him. I can do about one Difficult Poet per decade so he’ll have to wait his turn.

Bolaño held Nicanor Parra as his country’s best; his Antipoems is readily available used but I haven’t got around to buying it.

Blanca Varela was probably Peru’s most acclaimed postwar poet. She had one posthumous English translation, Rough Song, that was in print for about 30 seconds in 2021.

Venezuela’s Alejandro Oliveros is another mentioned as a Greatest Living Something. The little I can find translated looks promising.

Oh yeah, and then there’s everyone born after 1951. I was impressed by Daniel Borzutzky’s recent translation of Paula Ilabaca Núñez’s The Loose Pearl, but I have little context to put Xennial Chilean feminist literature in besides like Mon Laferte.

***

Olivia Rodrigo live: a two paragraph review

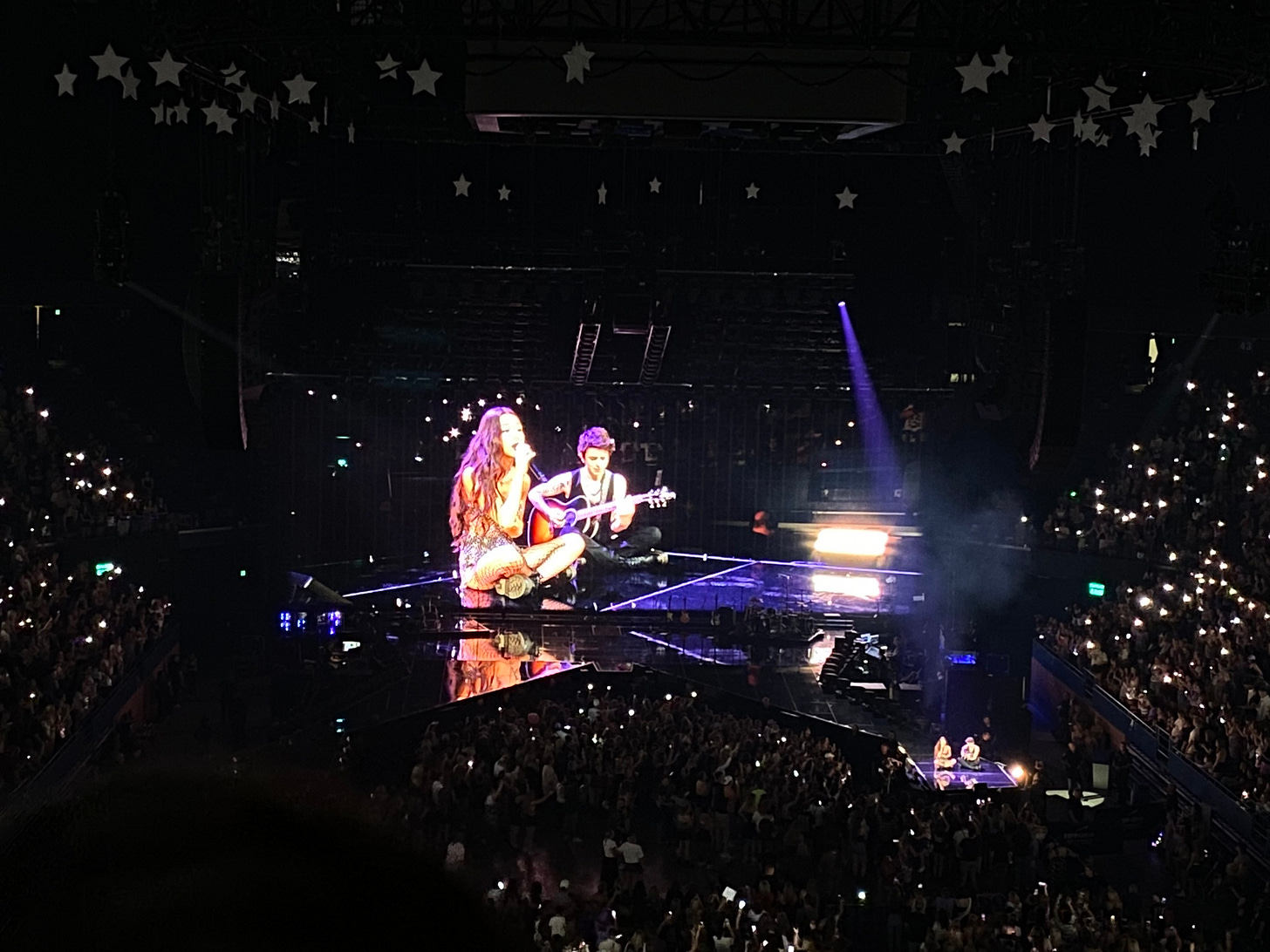

We won the lottery to pay Ticketmaster to sit a basketball court away from her at the Rupp Arena in Lexington, which gave the impression of being a terrible music venue except maybe for this specific show. We got 20 minutes of PinkPantheress as our opener—her job was to temporarily inflate her bedroom breaks to arena size and get out of there before anything popped, and she did fine (she’s since dropped out of the tour; best wishes to her.) Plenty of the superdupermajority teen/tween girl audience (accompanied by a few parents and the odd couple half my age who must’ve felt old for the first time) were singing along to “Boy’s a Liar”, but that was nothing compared to the main event. It was probably the most ear-splittingly loud audience I’ve ever experienced; it seemed like almost everyone knew the words to even the likes of “Obsessed” and “So American” and just shouted them, tune be damned. Correspondent Jonathan Haynes, who saw the Nashville show, compared it to guys in the back of the bus circa 1987 “reciting the lyrics to Run DMC and The Beastie Boys in unison. No passion or music in it, really—just chanting. Prayerful in the routinized sense of the term.” I think there’s something in this even if both Jonathan and I think “no passion” is too strong here. In any case, that doesn’t imply a lack of engagement with the text or the music; that’s already happened between AirPods. Olivia isn’t exactly a role model—she sings about relationship particulars that no one wants to go through. Perhaps what she represents for her younger audience is a way of processing strong emotions: whatever life throws at you, you can shout back “fuck it, it’s fine” while your slightly disconcerted mom is sitting next to you.

But then Tyler Childers showed up as a surprise guest and the kids knew the words to “All Your’n” as well. Maybe they’re all just music nerds.

***

Nineteen days left to vote in the 1974 poll! Details here.

Halfway through, I thought, now here's a guy who's going to enjoy Nicanor Parra!

I need to get serious about Paz myself, but I'll note that his book about Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz is wonderful, and the various translations of Sor Juana are quite good, if you want to extend your list to what I admit is a different tradition. But she really is a fascinatng person.

Very, very useful! And of course wonderfully written. Let me know when you grab that Nicanor collection--that's the only one you mention that I've read in full!