A grand Central degustation

Not the worst best restaurant in the world; plus other good eats in Peru and Colombia

Until this past Wednesday when, like Miss World, its reign mandatorily ended after a year, Central Restaurant in Lima was the best restaurant in the world, at least as voted by the 50 Best electorate of chefs, food writers, and “well-traveled gourmets”. Designating any one restaurant as “the best” is ridiculous, of course—especially when the criteria for becoming a voter don’t include, say, having ever been to Asia—but the honor has had consequences. Central’s prices have something like quadrupled since I started planning a Peru trip for 2020 (yeah, that one didn’t work out.) To get my required date, I had to hit refresh repeatedly on the day bookings opened four months in advance, finally getting through at 5 am. As someone who has never in my life earned six figures, it might not be the most prudent (let alone effectively altruistic) use of my money to spend somewhat more than one percent of my annual household income on one meal, but whatever, it’s more sensible than buying a new car. The price did mean that nobody eating in the dining room looked like a local, however. Central’s chef, Virgilio Martinez, has been criticized for his elitism—mostly by academics writing in English, which is ironic, because never has a restaurant felt more like an interdisciplinary grad school seminar than Central, with each course preceded by an educational display and a spiel on the ingredients by the servers. As someone who enjoyed grad school so much I spent almost the entirety of my twenties there, I’m very much the target audience.

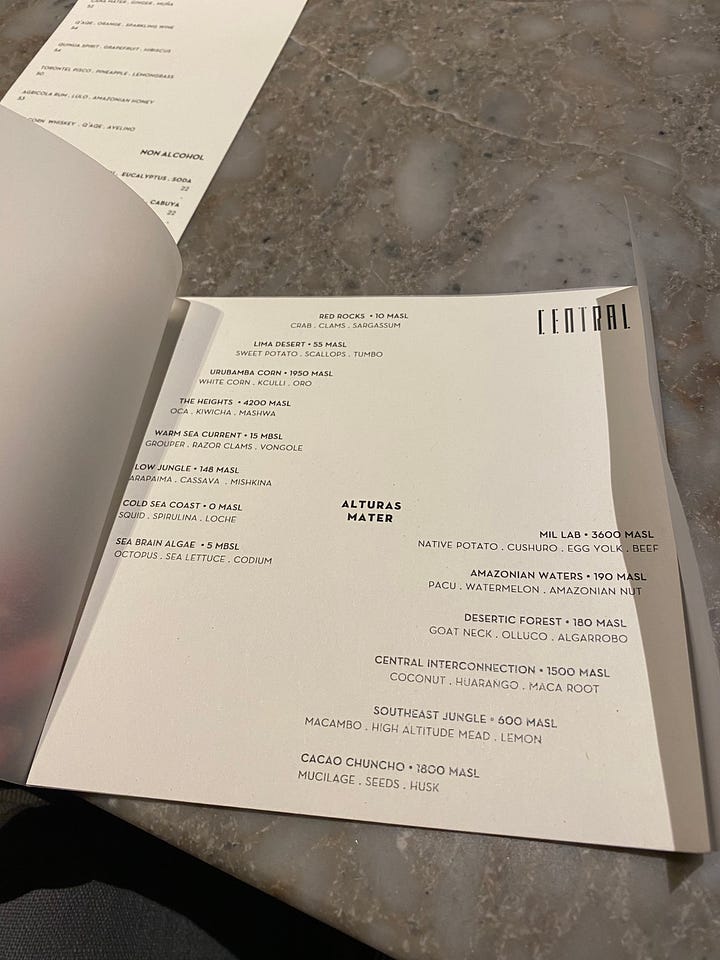

It’s not really possible for even the most unrepentant listmaker to designate the tastiest restaurant in the world—how do you compare a foam-mostly molecular meal to a great khao soi?—and anyone who tried to eat everywhere on a given 50 Best list in the space of a year would, if they stayed sane, start to miss real food anyway. So a contender needs… a tasting menu, but secondly a gimmick, and Central’s is a great one: the courses are organized (not ordered) by altitude. (We had the Alturas Mater menu, for the record, because it seemed substantially more interesting than the recommended Mundo en Desnivel choice for newbies.) Like all representations of an inherently multidimensional coordinate as a single number, giving the height is reductive: 180-190 meters above sea level could put you in a desert or in the Amazon. But in a country with the topography of Peru, it isn’t completely irrelevant, at least compared to peer restaurant gimmicks like writing a menu in emojis or serving food in a skull. So at fifteen meters below sea level, we had “Warm Sea Current”, which consisted of a lobster ball wrapped in seaweed, and a grouper crisp topped with clams served in a super-savory viscous broth. Immediately preceding that was “The Heights”, from 4200 meters up, where the pickings are slimmer; among the few agricultural plants that high in the Andes are native tubers like oca and mashwa, and the amaranth grain kiwicha, an alleged superfood. Regardless of one’s personal taste, it’s a remarkable achievement of marketing: getting the moneyed classes to appreciate something that’s mostly starch as a rarity.

That the result was delicious should be surprising only to those afraid of untranslated words on an ingredients list. Human preferences vary, but for the sort of people who go to fancy restaurants that aren’t just serving, like, steak, there are very basic taste commonalities one can rely on. So there was a lot of umami: who doesn’t like umami? Textures, too, were broadly crowd-pleasing. There was plenty of crunch, often used as a contrast, like the achiote spots sprinkled over fish belly in a herb salad in “Low Jungle”, sometimes there for its own sake (one way to make a relatively plain starch interesting is by turning it into a crisp.) There were luxury ingredients like sea urchin; elsewhere, non-luxury but tasty ingredients like goat neck were made as easy as possible to eat.

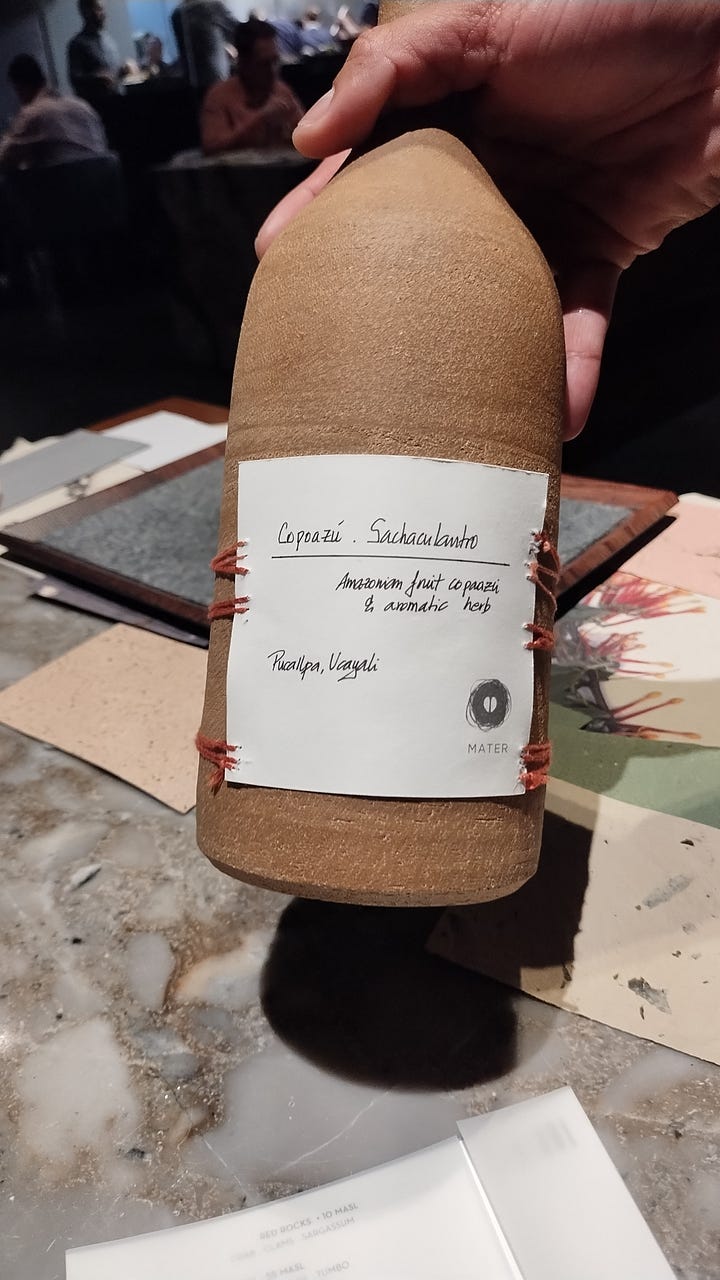

Perhaps things were a little too easy. I don’t know how things were before Central started getting best in the world talk, but at our meal there was little that was challenging about the food, the “will this be on the final” level of information provided notwithstanding. Closest was the cushuro, an Andean algae that takes the form of boba-like bubbles of varying sizes. It’s definitely weird, but the taste is so mild it’s hard to imagine anyone finding it objectionable. My one disappointment of the night was when the “Amazonian Waters” dish came out accompanied by the well-preserved heads of four pacu, piranha-like fish with oddly human-like teeth. For just a moment, I felt a rush of excitement that I would actually get to eat fish heads, before realizing they were display-only. Much more challenging than the meal proper was the non-alcoholic beverage pairing. The drink made out of the cacao relative copoazú and the herb sachaculantro, for instance, was genuinely strange. Some people might hate it! But that’s the kind of risk that I wouldn’t have minded the food taking more often.

So what did we end up with for our 3500 Peruvian soles? A full belly and an education, for sure. A better education than what we got from eating at much cheaper places around Peru for two weeks? Not really, but it was much more compressed, and covered parts of the country we didn’t get to (notably the Amazon.) It could’ve been more challenging, if not to the palette then at least to the mind, with more sociology to go with the geography: how does the employment of ingredients here compare to local usages by those who can’t put a full person-day of labor into a tiny dish? But I realize I’m in the minority here (again: nine years of grad school), and shouldn’t complain too much when there was some intellectual component to accompany the uniform deliciousness. Is it the best restaurant in the world? Probably not, but it’s not the worst choice for the best.

Arbitrage opportunities

With the best places in Lima now comparably expensive to places of similar prestige in the U.S., the Western Hemisphere’s best opportunity for bargain innovative dining might now be Bogotá. We went to Mesa Franca and El Chato, within a few blocks of each other in the less grungy part of the Chapinero. El Chato’s the one recently promoted to 25th in the world on the 50 Best list, probably because it has a tasting menu that we didn’t try. Ordering smaller plates a la carte, we found the two quite comparable, with maybe a slight edge to Mesa Franca. A fair comparison would be Rose’s Luxury in D.C., though these places are a quarter of the price.

As usual, there was plenty of savoriness. At Mesa Franca we had a squid ink fish rice dish that was marvelously black and a total umami bomb, and a lamburger was correctly (i.e. heavily) salted. One advantage of not having a best-in-the-world position to defend, however, is one can take a bit more risk with tastes and textures. Mesa Franca’s standout dish was a watermelon “tartare” that, eschewing meat, had a unique texture as well as an unusual taste. An otherwise pedestrian mushroom noodle dish was enlivened by bok choy that had a bit of bitterness to offset the glutamate fatigue. Plus the meringue for dessert came with soursop that was recognizable as soursop. Hopefully every now and then some Yankees faint at the smell of it. An insanely gingery lemonade was maybe the most memorable drink we had outside of Central.

Mesa Franca seemed somewhat disorganized (but for seventy bucks for two, who cares.) At El Chato, since it aspires to be on The List, the service was much better and the outfit generally more professional. The cooking nodded a little more towards the European classics: there was a pork terrine, for example, again with offsetting Chinese cabbage bitterness (though the leaves should’ve been cut smaller or else we should’ve got sharper knives.) We also had a Tuna Wellington in a rich beurre blanc. Sauces in general were a highlight: slices of lamb saddle came in its own slow-extracted gravy. (I did like that the lamb still had some connective tissue attached to it; hopefully not all the good bits get excised from the menu as the restaurant rises through the ranks.) But even simpler dishes like crab with peas or dessert ice creams showed off the freshness of the ingredients and the kitchen’s skill at concentrating flavor.

Also above the trip average

Kudos to Gastón Acurio, godfather of Peruvian celebrity chefs, for bothering to show up to lunch service at his Lima cebicheria La Mar. Ceviche in Peru is always delicious thanks to a fish freshness that isn’t really possible in the contiguous U.S. outside of ultra high-end spots, but can get a little samey. La Mar solves this by offering up all kinds of unchilled seafood: I’ve never had so much sea urchin in my life. (The other memorable ceviche I had was at El Mochero in Moche near Trujillo; I think the fish was cheaper than the usual ceviche white fish, resulting in something softer, more slippery, and more texturally interesting.) His smaller El Bodegón serves comfort food in perhaps the largest portions I’ve encountered outside of an elderly Chinese woman’s dining room. A lot of the classic Peruvian dishes aren’t exactly things you’d want to eat more than once on a trip (hello, lomo saltado) but “vegetable stuffed with non-vegetable” is a safe bet, and El Bodegón’s zucchini relleno was probably the most sophisticated of these.

Anticuchos de corazón definitely fall in the “you don’t have to have them that often” category, so you might as well get the best. Grimanesa Anticucheria is on the opposite corner to La Mar; Acurio helped with the initial financing and his picture’s on the wall (you can see why he’s more universally beloved than Virgilio Martinez.) Grimanesa’s skewered beef hearts were very heavily seasoned and unquestionably delicious if you like offal at all, though not for the, uh, faint-hearted (there’s also chicken if you’re chicken.) Organs-on-a-stick were also the form taken by the best Asian-qua-Asian food of the trip, at Reiwa Yakitori in Barranco; in addition to chicken livers and gizzards, it’s a fine way to enjoy the inherent quality of the local produce (the asparagus was notably good.)

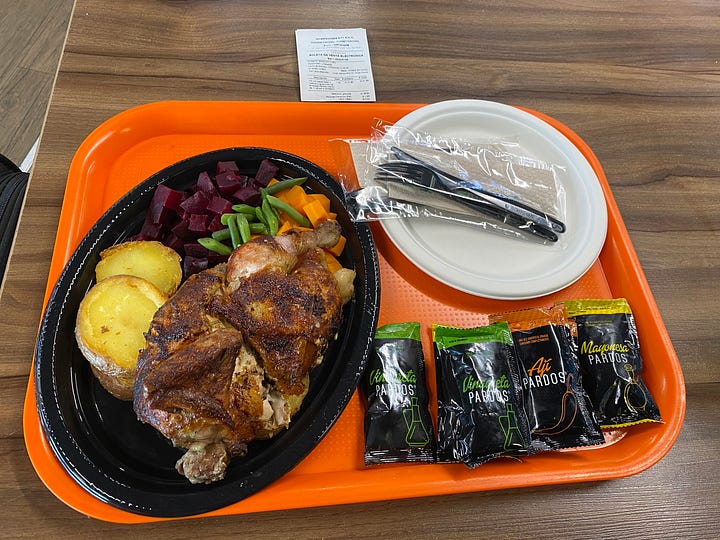

You’ll probably end up at Lima Airport a lot, so you might as well enjoy what’s probably the world’s best airport food court multiple times. The Pardo’s Chicken there has its rotisseries spinning in full view of the ensuitcased travelers; their pollo a la brasa was at least as crispy-skinned as at more renowned places we went to, and if the aji amarillo sauce comes from a packet and has a bunch of preservatives in it, it’s still delicious. La Lucha has very good sandwiches, fries made from the elusive huayro potatoes, and as-good-as-anywhere chicha morada. Hell, even the fried chicken from McDonald’s is of a quality you’d need to find one of the good Popeye’s to match.

Food quality and probably food safety are significantly lower in Cusco and the Sacred Valley compared to Lima, but good eats can be found. The two that were memorable were Chuncho in Ollantaytambo and Pachapapa in the San Blas neighborhood of Cusco. Chuncho had a banquet for two that apart from being the best way to try guinea pig (better grilled than fried, and even then it’s not so interesting that one needs much of it) also had excellent fatty lamb and interesting desserts, as well as the best big-kernel corn of the trip. Pachapapa had the old reliable stuffed vegetables (rocoto rellenos, one extremely spicy, one less so) and meat on a stick (this time alpaca); pizza wasn’t great as pizza but was fine as a smoked trout delivery system. Cusco’s Three Monkeys produced the best coffee of the trip: a locally-grown Gesha (for five bucks!) I hadn’t had a Gesha since it first became fashionable in snob circles circa 2007; glad they’ve worked out how to make it taste like coffee now.

In Bogotá, we, like everyone else in town who watched Anthony Bourdain, went to the 200-year-old La Puerta Falsa for tamales, plus hot chocolate in which to dunk one’s mozzarella. The intensity of flavor was achieved using the expediency of pork fat, but whatever, it was delicious. Hard to compare to the best Mexican-style tamales I’ve had (I think they use cornmeal and ricemeal rather than masa proper), let alone the rest of Latin America. If someone wants to fund me a research trip, I would not decline.

Sources: Robert C. Bradley’s Eating Peru is an excellent book that combines specific recommendations with some reasoned discussion of the botany and politics of the nation’s cuisine. It might be a bit more advanced than a first-time visitor to the country might like (the ideal reader is someone with the inclination to rent a place on the north coast for a month and work through the fish market species by species), but the lay audience should get something out of it for a fraction of the price of a near $1000 meal. Of the many printed travel guides I digested, Fodor’s was the most useful for food and more generally. Two quite different Substacks, New Worlder by Nicholas Gill (who co-wrote a couple of Central’s Virgilio Martinez’s books) and the more informal How to Eat in Peru by Sutee Dee were both worth paying for, even if I’m going to unsubscribe to both of them tomorrow.

Looks very good!