I have no real qualifications other than I’ve been reading this stuff for a long time—since half of Borders’ manga shelves were Ranma 1/2 (good series.) The nature of the list is biased towards action/adventure shonen titles, which are much more likely to be partitionable into discrete chunks. There’s no Mizuki or Tezuka, possibly still the two greatest mangakas, and no shojo at all. (If I did a list of one-shots, Sailor Moon’s Princess Kaguya retelling would’ve done well, though Fujimoto probably would’ve topped that list as well.) Also there’s no JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure because it’s ugly and I hate it. Onward!

1. Chainsaw Man #1-97: Public Safety (Tatsuki Fujimoto)

Yeah, you might’ve seen this coming.

Regression to the mean implies there’s almost no chance the just-begun season will be as good, and yet:

2. Hunter x Hunter #64-119: Yorknew City (Yoshihiro Togashi)

This list is one per series, or else the Chimera Ant arc, which ticks off more Literary Value boxes, would be number four or five as well; I prefer Yorknew because it’s more compact (it didn’t take a decade of real time to complete.) HxH has such a different rhythm from any other shonen action title: in 24 years, only one of the story arcs has ended with the protagonists straightforwardly defeating the bad guys. This isn’t that one: in Yorknew City, tweens Gon and Killua need to raise billions to buy a magical video game to find Gon’s father, and not only do they not get the money, they don’t do much at all besides get captured a couple of times. The major fight happens halfway through and the foreshadowed big showdown never happens. Dozens of distinctive characters are introduced, and the reader has no way of knowing which will become major players and which will be killed off in a few panels. Togashi’s art is unapologetically cartoony, scratchy with heavy use of blacks, and if you like the look of old newspaper dailies more than, say, Alex (not that one) Ross, you might prefer it the art of much of the rest of this list.

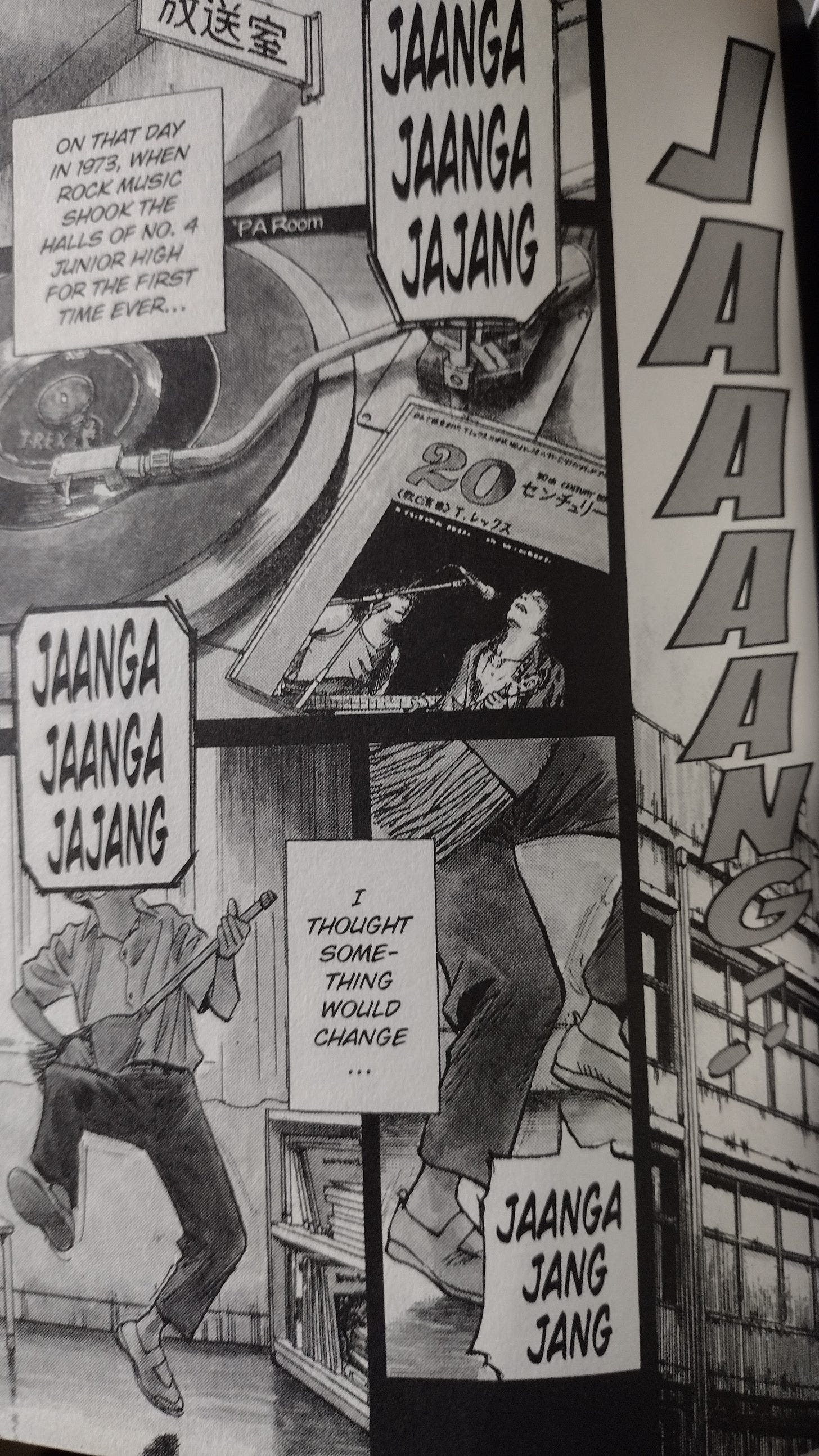

3. 20th Century Boys #50-169: 2014 (Naoki Urasawa)

Designating this as an arc is arbitrary—it’s the section set in 2014, except lots of it is flashbacks anyway—but it’s the greatest run by one of the major mangakas. The obvious parallel—a time-jumping narrative of childhood friends reuniting to fight evil—is Stephen King’s It. The moment-to-moment plotting is similarly strong, but this is much richer: nostalgia isn’t just taken at face value (even as its seductiveness is acknowledged.) Failing to grow up may be the worst sin of all. If you get through the arc, you’ll probably want to read through to the ultimate boomer ending—how do we save the world? by putting on Woodstock!—famously botched as it is.

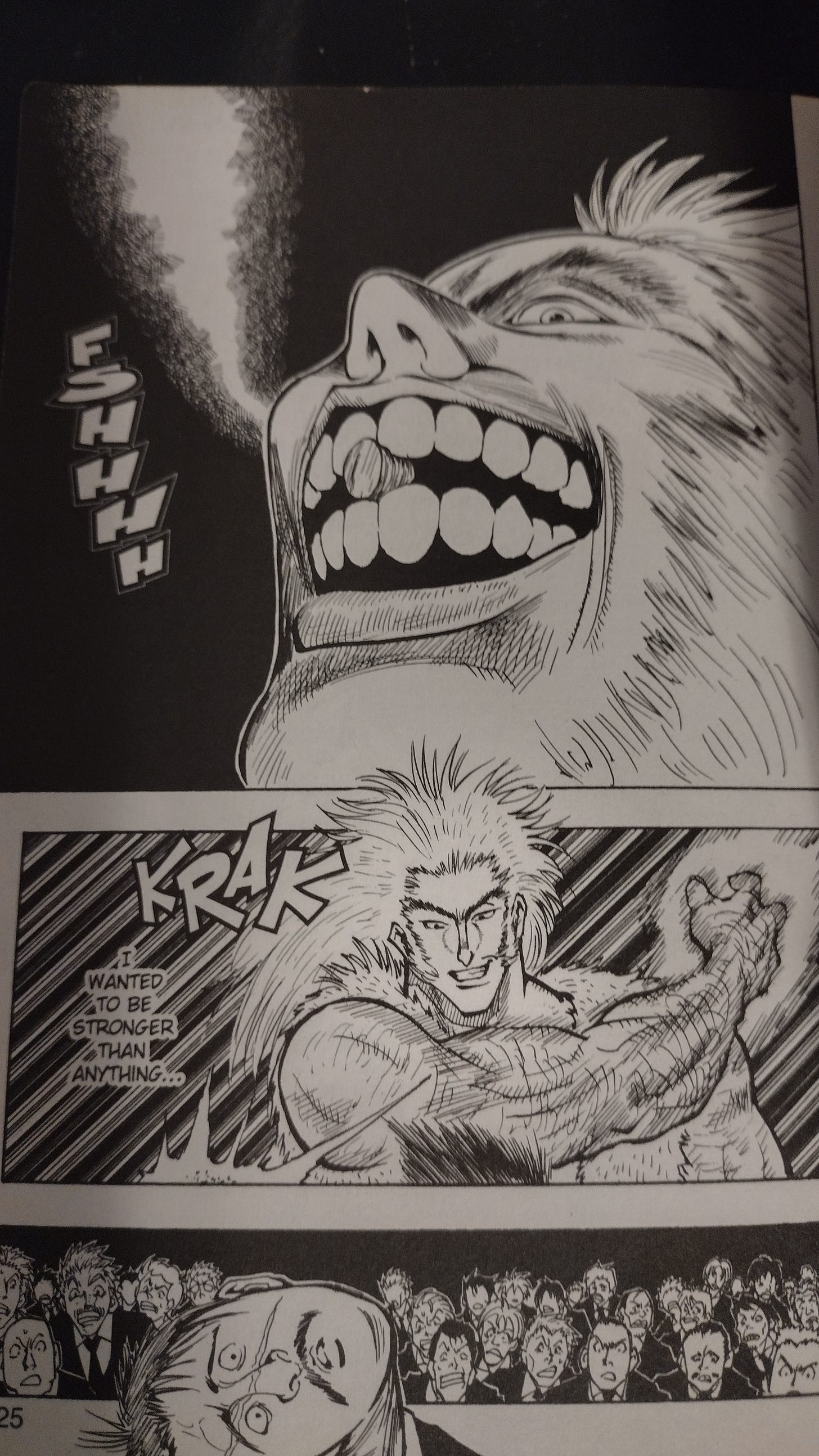

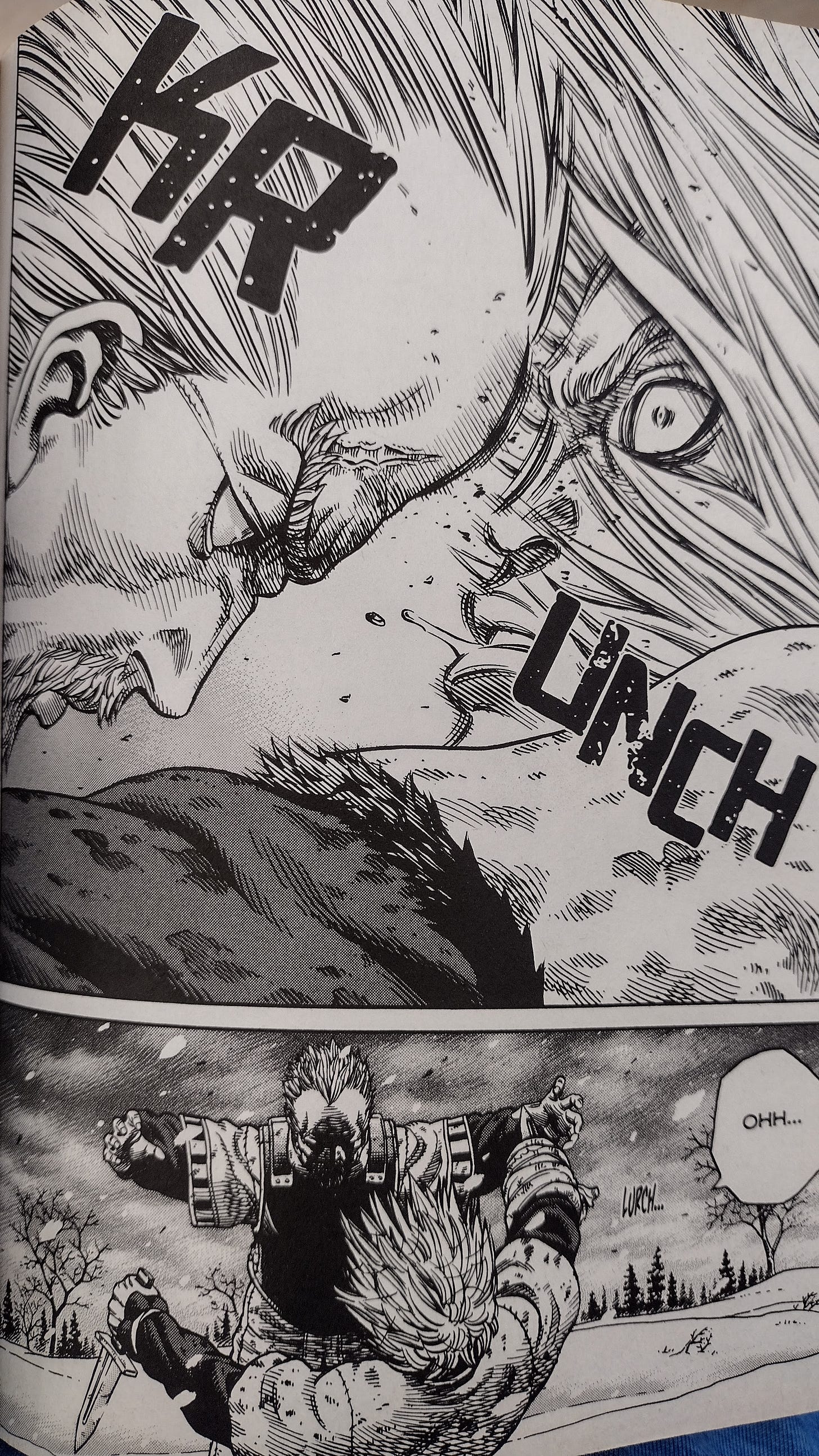

4. Vinland Saga #1-54: Prologue War (Makoto Yakimura)

The most Western of major mangas, mostly because it’s about Vikings but a bit because it’s so violent. Among Western adult fans of manga, who are into the genre for the dismemberment if not for less savory reasons, the consensus GOAT series is Berserk. I took another shot at reading it as due diligence for this list, and while I recognize the dynamism of the art and plotting, Guts is kind of a lunk. So, initially, is Thorfinn, Vinland Saga’s young Viking protagonist, but he’s a kid, a reasonable excuse. Yakimura’s violence is stylish yet never allows you to get entirely comfortable with it. The arc ends with perhaps the genre’s greatest plot twist, worthy of G.R.R. Martin, which unexpectedly transports the story into an entirely different moral universe. It would be ideologically convenient to say the series gets even better from there.

5. Dragon Ball #242-329: Frieza (Akira Toriyama)

Those who, like me, first encountered this through the anime might be surprised to learn how efficient the manga’s storytelling is. The infamous last five minutes on Namek, which takes three hours of TV time plus commercials, lasts a much more reasonable (if still drawn out) nine chapters on paper. That aside, it’s hard to overstate the influence of this: martial arts and aliens and ki blasts and transformations and death and resurrection had all been done before, but here they are all at once.

6. One Piece #322-430: Water 7/Enies Lobby (Eiichiro Oda)

I wrote a bit about One Piece in my chronologically ecumenical comics of the 2010s list, but I want to reiterate what makes Oda stand out is his aptitude with the mechanics of narrative: the ability to engineer a shining moment for each of the heroes, including the ship. That all of the characters are so visually distinct—Reindeer Guy, Cyborg Guy, etc.—surely helps.

7. Haikyu: Spring Tournament (Haruichi Furudate)

Issue numbers omitted deliberately. With most of my picks, you can read the first chapter of the series to grok the premise, then skip to the arc in question without missing much; you can always go back later if you care. If you’re going to read Haikyu, however, you should it read start to finish, both because of its plot format—two single-elimination tournaments during the 2012-13 Japanese high school volleyball season—and because it has the rarity of actual character development that aren’t just the characters reacting to events (well, technically they are, but the events are things like “blocking a volleyball.”) Furudate always keeps Charlie Brown’s “how did the other team feel” in mind, meaning he gets across the homosocial ecstasy and existential but also physical agony of competitive team sports better than anything I know, although I’ve only read a tiny bit of Slam Dunk and should rectify that one of these days.

8. The Promised Neverland #1-37: Jailbreak (Kaiu Shirai & Posuka Demizu)

Beats out the first half of Death Note for the best chessgame “he knows that she knows that he knows” storyline because there’s no serial killing. The rest of the series isn’t nearly as clever—it’s rarely clever at all—but by then you might be so attached to the characters that you end up reading the whole thing anyway.

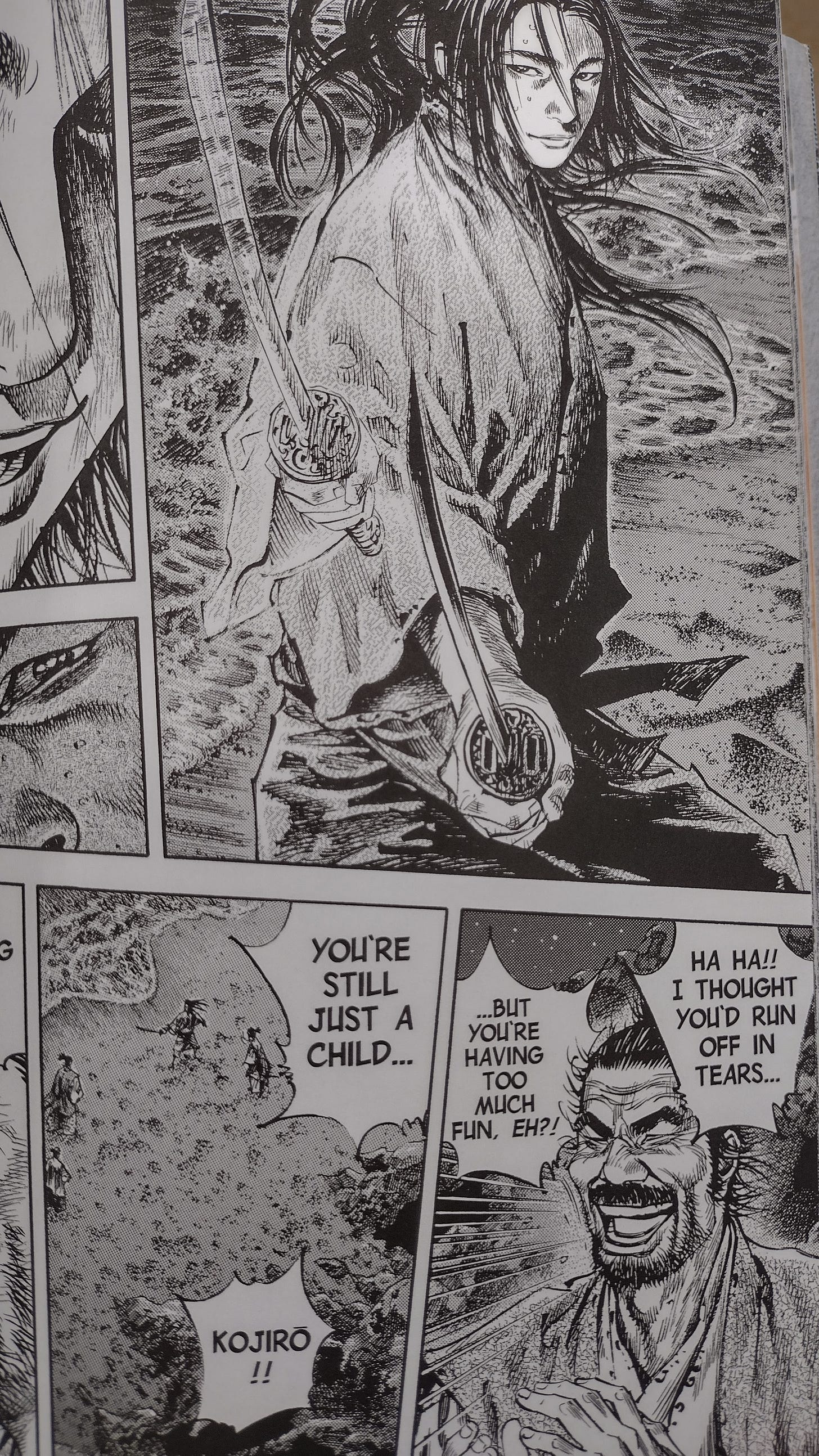

9. Vagabond #128-179: Kojiro (Takehiko Inoue)

For someone who doesn’t share the values of early Edo samurai, the dialogue in Inoue’s unfinished retelling of the life of ronin Musashi Miyamoto can get a little “well I’m getting cut up for no good reason, but at least I lived by the sword.” The Kojiro arc, focused on the formative murders of Miyamoto’s great rival, avoids this problem by portraying Kojiro as deaf-mute, letting you focus on Inoue’s best-in-the-biz brushwork and see that the guy cutting people up is, in fact, having more fun.

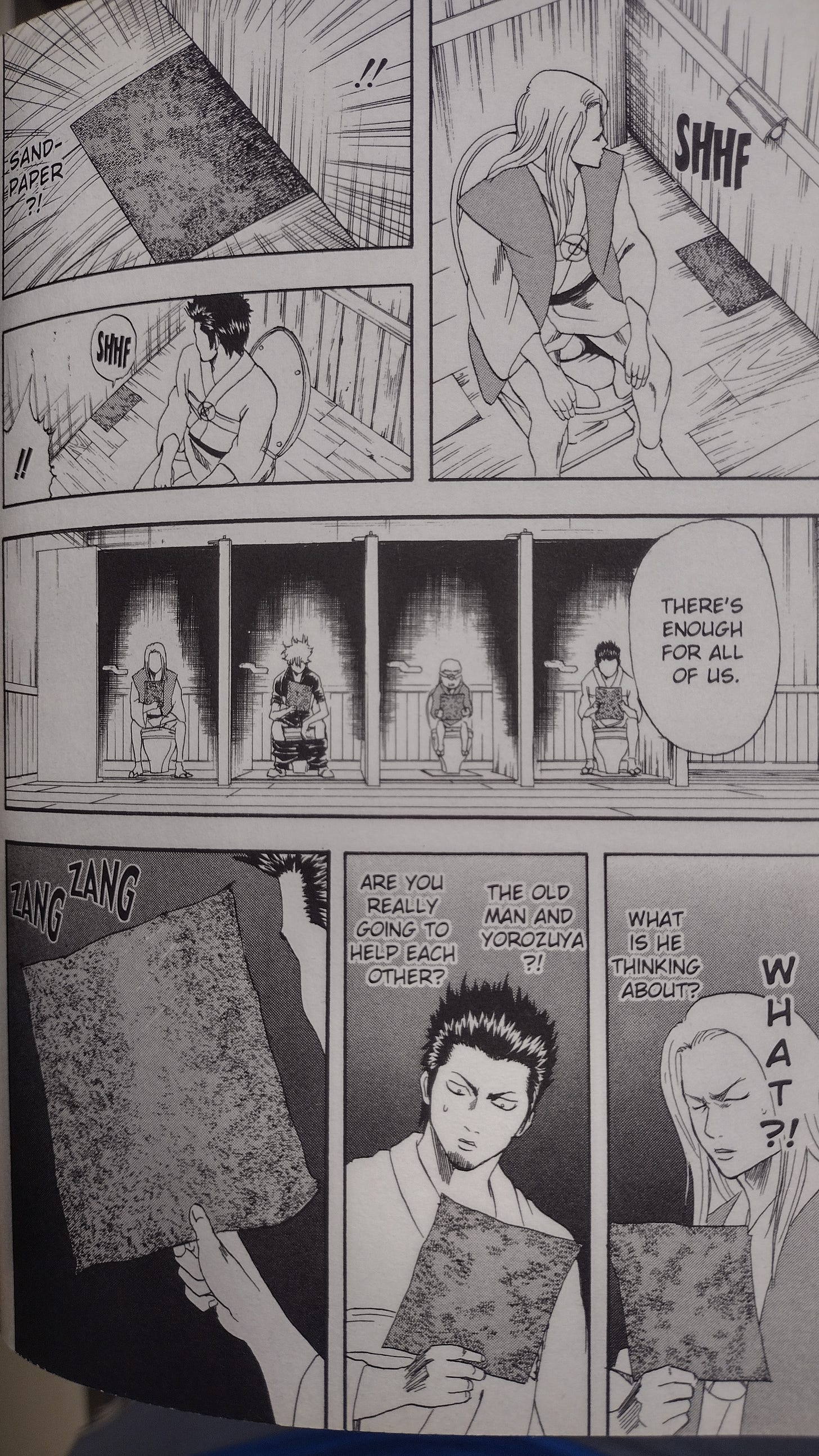

10. Gin Tama #110-123: Yagyu (Hideaki Sorachi)

Like every other long-running shonen title, Gin Tama eventually became a fighting-mostly series, but in the earlier years it combined its action with the best literal toilet humor since Trainspotting.

Also worthwhile:

Hikaru No Go: Pro Exam (Yumi Hotta & Takeshi Obata)

Attack on Titan: War for Paradis (Hajime Isayama)

Death Note: L (Tsugumi Ohba & Takeshi Obata)

Rurouni Kenshin: Kyoto (Nobuhiro Watsuki)

Demon Slayer: Entertainment District (Koyoharu Gotouge)

One Punch Man webcomic: Monster Association (ONE)

Fullmetal Alchemist: Promised Day (Hiromu Arakawa)

Naruto: Pain’s Assault (Masashi Kishimoto)

Yu Yu Hakusho: Chapter Black (Yoshihiro Togashi)

Black Lagoon: Fujiyama Gangsta Paradise (Rei Hiroe)