As has often happened with these decade lists, I thought I had done a good job keeping up with comics until I checked against other people’s lists and found all sorts of intriguing stuff I wanted to read. In the end, I think I did well enough at covering English-language comics despite some holes at the microindie and zine level (I read none or not enough of John Hankiewicz, Tim Hensley, David King, John Pham, and especially Lale Westvind, who at the extreme end of the decade seemingly everyone suddenly decided was one of the era’s defining artists, and looking at pictures on the Internet doesn’t exactly prove them wrong.) There’s also decent if non-comprehensive representation of manga, in part through my usual flexible definition of “decade” (if the official English translation was completed in 2010 or later and I felt like including it, I could.) As for the rest of the world, I look forward to spending subsequent decades finding out what I missed.

1. Emil Ferris: My Favorite Thing Is Monsters (Fantagraphics)

No pressure or anything, but this is on pace to compete on the GOAT tier with Krazy Kat or the half of In Search of Lost Time I’ve read—the reimagining of half the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago alone would make for an astonishing achievement. Ostensibly a murder-mystery that, Katamari-like, accumulates additional mysteries as the Sixties roll on, the narrative becomes “let’s just put all of the twentieth century in there” dressed in a bewildering mix of genres. Every page demands to be stared at, yet the work is unified by ruled lines, upward-pointing fangs, a blue face. Keep HBO away from it, at least for a while, please.

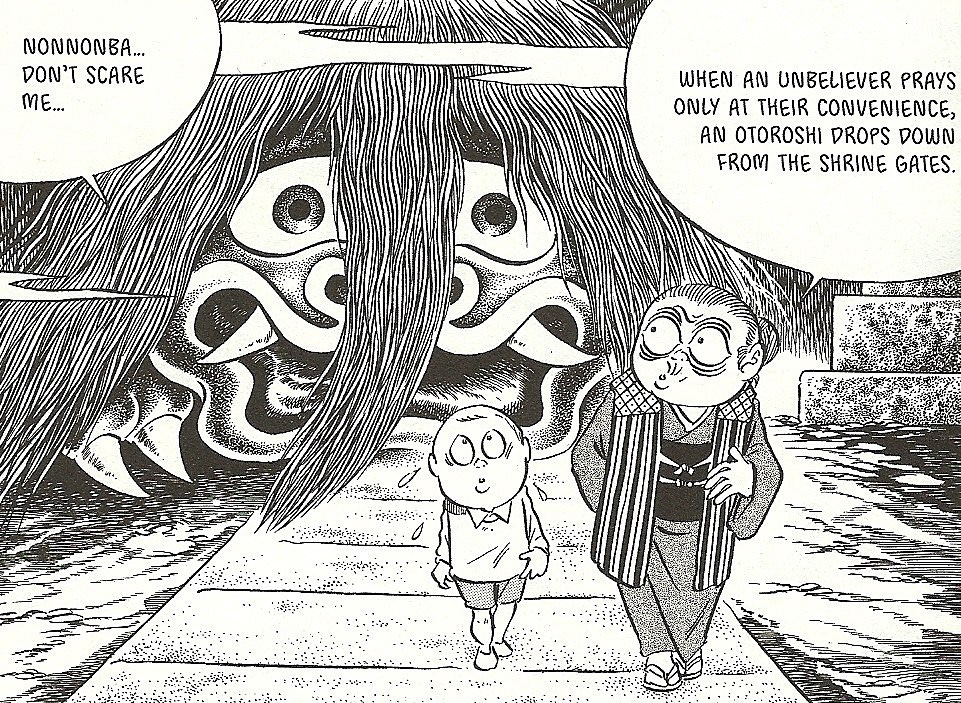

2. Shigeru Mizuki: Nonnonba (Drawn and Quarterly, trans. Jocelyne Allen)

A much more approachable starting point to a manga legend than his 4-volume Showa (which requires you to know a bunch of Japanese history to work out how reasonable his interpretations of Japanese history are.) There are fantasy elements, with yokai showing up to help, annoy, or just confuse young Shigeru and his de facto grandma, but much of the evocation of early ’30s family life and childhood hijinks are as realistic (in attitude if not drawing style) and haunting as I Was Born, But…, only here the author knows the boys playing at war will be on the wrong side of a real one before too long. Not that Shigeru has to wait that long to see suffering and death, what with a Depression going on and slavery not as extinct as one might hope. It’s not right that Shigeru gets time to come into his own while the girls that drift in and out of his life have to be as self-possessed as a Setsuko Hara character from the beginning. But it’s the story.

3. Anders Nilsen: Big Questions (Drawn and Quarterly)

I promise you these aren’t all going to be Learning About Death Comics and we’ll get to some light stuff around #6, but while we’re doing this, this is an especially fun Learning About Death and Perhaps What Lies Beyond Comic. Over 600 pages, Nilsen works out that visual storytelling is a philosophy in itself, as he mixes images of destruction and despair with drawings of cute finches, preternatural swans, and loquacious yet lightweight skeletons. Greek myth, winged romance, clobbering time, living with snakes, chocolate or peanut donuts: these birds will build nests out of anything.

4. Taiyo Matsumoto: Sunny (Viz, trans. Michael Arias)

The Sunny is a stationary yellow Nissan that’s a locus of fantasy at a Yokohama home for orphans and children otherwise cast aside by their parents. The series seems a bit samey at first but eventually gets really good, with moment-to-moment happiness expressed through the foster kids’ fascination with the period details (I can vouch for the ’70 Japanese pro wrestling references) glossing over their existential emptiness that comes with no longer knowing how to be loved. The chapters on an orphan girl being wined and dined by her uncle and aunt and on a nerdy boy's plans to drive off in the Nissan Sunny of the title are Edward Yang-good. In the ending, life drives on.

5. Eleanor Davis: The Hard Tomorrow (Drawn and Quarterly), and How to Be Happy and You & a Bike & a Road and basically everything she’s done

The Hard Tomorrow is where her evocative lighting and characterization through poses and shapes achieve an insight worthy of the best cartoonist in the world. It captures better than almost anything I’ve read the perils one faces when trying to be a decent, moral person in a country that still hasn't yet hit maximum fjucked-upness (the President is Zuckerberg.) You can turn to activism, and for all the betrayals and abandonments and physical and emotional beatings you’ll take, nothing hurts as much as discovering that perfectly funny and cool people are on the other side. Okay, maybe the abandonments hurt more. Still, the alternative—going off grid to maybe grow a little weed or work on your deadlift—is going to mess you up worse. It’s all fucked, it’s all good.

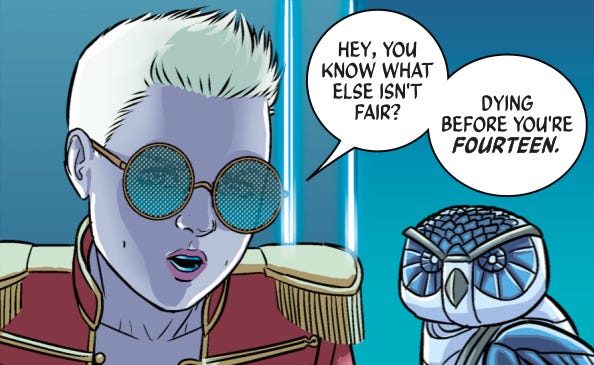

6. Ryan North/Erica Henderson/Derek Charm et al.: The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl (Marvel)

The multi-issue storylines are fine—there’s usually some miscommunication that hero Doreen Green resolves through “cosmic-tier empathy and understanding” and maybe a suit made of squirrels or squirrel clones. Their main pleasure is in the peripheral details they enable: the footer notes! Deadpool’s trading cards! Alfredo the Chicken! Kraven the Hunter finally getting a half-decent characterization after all these years! The one-shots can be even more unbeatable: getting Jim Davis to draw a funny Galactus strip is some cosmic-tier meta-comical japery, even if/especially because it isn't funny. Easily Marvel’s best effort in a decent decade for them.

7. Jillian Tamaki: SuperMutant Magic Academy (Drawn and Quarterly)

That J.K. Rowling turned out to be one of those people makes this sympathetic yet very funny collection of gag-strips-oh-look-now-it’s-narrative more magical. What if you’re not the chosen one, and your dork glasses and your unrequited crushes aren’t going to be validated by you saving the world, and what if a cat monster eats you anyway? What if, despite your immortality, your body continues to shock you by finding new and gross ways to express itself? What if your norm-breaking performance art has, like, been done? What if your boyfriend is a little too into alternative comics? Teenaging, man.

8. Jaime Hernandez: The Love Bunglers (Fantagraphics)

With a few exceptions (notably Frank King), the great multidecade comic runs of the past didn’t really do character development: Ignatz kept throwing bricks and Charlie Brown kept missing the football. So Jaime continuing to have meaningful things to draw about Maggie and Ray and their crews is near-unprecedented. Here, he twice plays out the endgame of three decades of punk intersectionality to crushing conclusions. And the ends aren’t the end: the subsequent Is This How You See Me? continued to have pithy insights into middle-aged punks and ex-punks.

9. Eiichiro Oda: One Piece #1-597: Super Rookies Saga (Viz)

The character balance is key: just look at the variety of reactions he gets out of the crew whenever a What Is It This Time event happens. And Oda is just great at giving the people what they want. Fight train? A food-themed enemy so Sanji can finally display his knife skills? Sure! Compare his megafight construction to Crisis on Infinite Earths or whatever your favorite Western comics free-for-all is, and see how well he handles his characters while retaining clarity. Add in the sublime-ridiculous emotional payoffs and you get the most ruthlessly efficient serial storytelling since Kirby/Lee, sustained for longer. And I still have another ten years of the series before I’ve caught up.

10. Kieron Gillen/Jamie McKelvie: The Wicked + the Divine (Image), plus let’s also mention Young Avengers (Marvel)

Gillen gets enough credit as the best mainstreamish writer of the era, so let’s first celebrate McKelvie: beyond the cool character designs spanning literal centuries of pop, his control of tone is amazing, from gimmicky panel structures to neon multicharacter splash pages straight outta Pérez. Still, people, Gillen: unlike some dialogue whizzes on and off this list, he’s capable of wrapping up the plots he sets into motion, and he takes the correct amount of time getting to his endings.

11. Tillie Walden: Spinning/On a Sunbeam (First Second)

Pretty bold to publish a 400-page memoir when you’re barely old enough to drink. There are no Taylor Swiftian claims that this is how everyone grows up: Walden portrays herself as isolated and kind of aloof, which is tough when your main after-school activity is synchronized skating. Spinning is great at evoking what it’s like to be a small person in a large space that’s at best largely indifferent to you (whether an ice rink or Texas) and also at capturing the excitement of the last Twilight book coming out. The even earlier coming-of-age-in-outer-space story On a Sunbeam is just as good: perhaps some of the art is a little green, but who cares when this depicts both wild sci-fi ideas and young women’s friendships with such vivacity and detail that Paper Girls looks like mere nostalgia in comparison.

12. Carol Swain: Gast (Fantagraphics)

Wales is different—you can talk to the animals, though they’re as high lonesome as the humans are. The story concerns a girl investigating the suicide of a “rare bird,” and if she solves what mystery there is well before halfway, she keeps investigating because there’s always more to learn. Swain’s pencil art uses shading brilliantly to express physical light as well as emotional light, making a restaurant in England look like the strange foreign territory that it’s become.

13. Yumi Hotta & Takeshi Obata: Hikaru No Go (Viz)

I mean if I were possessed by the ghost of the greatest Go player ever, I’d get pretty good too. The distinctive super-styling characters make kids putting stones on a board feel like 5-5 OH MY GOD HE PLAYED 5-5. And the finishing stretch ignores the conventions of shonen manga for unclear reasons, and then it just ends, a great arthouse move. A moving coming-of-age study, capturing both the excitement and the nagging sense of loss that come with passing into the adult world.

14. Chris Ware: ACME Novelty Library #20: Lint (Drawn and Quarterly)

You might as well get this as part of the somewhat annoying collection Rusty Brown, in which Ware, an absolute master over his house style, partially wastes it on by now rote slices of the lives of sympathetic losers while totally wasting it on slices of the lives of unsympathetic losers. The exception is this birth-to-death chronicle of total asshole loser Jordan Lint, which sees Ware pushing himself harder formally while delivering a trickier-than-his-usual narrative.

15. Jason Lutes: Berlin (Drawn and Quarterly)

A decades-in-the-making masterpiece according to some literary types. I might not go that far, but this is four pounds five ounces of major work. In the run-up to the Nazis taking over, every side is depicted as fjucking up both strategically and morally, and given the outcome this seems fair enough. Perhaps more interesting than the politics is the city-symphony aspect, with workers and bohos flailing about trying to get on with their loves and lives. Plus: the best visual depiction of music I’ve seen in comics.

16. Bill Griffiths: Invisible Ink (Fantagraphics)

The creator of Zippy the Pinhead tells the often batshit story of his mother’s long affair with, oh come on, really, a cartoonist. Griffiths finds a new angle on the now much-covered repression of women in the ’50s, and his perspectives of New York and its ’burbs are lovely, but the meta-elements arguably have more value: how much does digging into the past change our experience of it?

17. Yusei Matsui: Assassination Classroom (Viz)

A tentacled yellow creature blows up the moon, then becomes the instructor of class 3-E at Kunugigaoka Junior High, the members of which must assassinate him by the end of the school year or he’ll destroy the Earth. What follows is one of the best works of fiction about teaching I've ever read, showing that the best way to reach your students is to be a perverted octopus with an eidetic memory who can move at Mach 20. Every character gets developed: such is a teacher’s job.

18. Joyce Farmer: Special Exits (Fantagraphics)

A major underground comic artist in the Seventies, Farmer spent thirteen years working on what’s a very traditionalist comic, severe in form and warm in content, about the illness of her parents. The focus is on the dignity that the dying deserve and don’t always get, and it’s not like indifference in nursing homes and low-level medical bureaucracy has become hard to find in the decade since this was published.

19. Anya Davidson: Band for Life (Fantagraphics)

This former weekly strip for Vice captures the modern not-that-young-anymore demimonde life through the travails of experimental-mental-mental band Guntit (maybe kinda not really based on Davidson’s band Coughs, who got a 6.5 in Pitchfork when that wasn’t considered an insult), who struggle to achieve self-actualization through noise amidst the pressures of wage slavery, kids, substance abuse, and vengeful rival tattoo parlor proprietors. It gets soapy at times, but it really is an acute portrait of a sliver of a generation: maybe the last pre-poptimist one that thought that activism and broadly-defined punk could and should be two sides of the same life.

20. Osamu Tezuka: Black Jack (Vertical)

Tezuka’s best-selling work in Japan, though many snobs prefer the wilder and messier time-hopping Phoenix. No mess in these twenty-page stories: the eponymous outlaw surgeon saves the day with just enough panels to spare to give fate a fair chance to wreck things again. In its ruthless efficiency and to some extent its tone, this reminds of the original Dragnet (the Fifties one, not the hippie-punching one), where a slight tweak to the formula is more seismic than a dozen Game of Thrones kill-offs.

21. Michael DeForge: Big Kids/Ant Colony (Drawn and Quarterly)/A Body Beneath (Koyama)

What do DeForge’s Tex Avery spiders and centipede cars and smiling maggot-ridden faces have in common? If you’ve read this far, you’ve probably guesses that it’s death, always death. Big Kids is probably his best: a gay boy turns into a tree and experiences all the angst and grotesquerie of growing up, in with more narrative and glorious pink and yellow beauty than is usual amidst DeForge’s habitually disgusting art, and you might even get the impression that his characters think life is worthwhile, sometimes. That doesn't stop them from being dickwads, though.

22. Jesse Jacobs: Safari Honeymoon (Koyama)

Horrors-of-nature comic, and since this is literature the real horror is people. A couple and a guide walk into a jungle, shoot some stuff, and just maybe achieve transcendence. Adventure Time veteran Jacobs’s weird creature art is exceptional and diverse, with Arcimboldean vegetation and DeForgean monstrosities that decompose into numerous smaller DeForgean monstrosities.

23. Allie Brosh: Hyperbole and a Half (Touchstone)

As representative of the blogcomics era as Kate Beaton (who gets screwed out of this list because I read most of Hark! A Vagrant in the 2000s, sorry.) But it’s also visionary, looking forward to a world of memes and crippling millennial depression and letting grammatical errors take on lives of their own. It’s not everything that happened in the 2010s, but it’s alot.

24. Emily Carroll: Through the Woods (Margaret K. McElderry)

Solid blacks and sanguine reds illustrate tales of mystery and imagination: playing Frankenstein with ribbons instead of electricity, relationships that outlast one kind of death or another, threatening a monster with visions of Canada. As gripping as whatever EC horror comic you can name, with plenty of bonus incidental feminism.

25. Drew Weing: The Creepy Case Files of Margo Maloo (First Second)

The character designs are amazing, with cutely schlubby Charles constantly in the shadow of the more brilliant Margo, who’s all points and sweeping cape and is basically Batman. The stories are more than good enough, with enough monster lore to fuel a wiki.

26. Jason Aaron, Kieron Gillen et al.: Star Wars: Vader Down (Marvel)

Not only the best Star Wars thing of the decade, possibly apart from The Mandalorian but probably not, but the best corporate crossover cash-in of the era, possibly apart from the first Avengers movie but again probably not. Helps that Aaron writes Gillen’s breakout antihero and her murder droids as least as well as Gillen does.

27. Grant Morrison et al.: Batman & Robin (DC)

Of course Bruce Wayne won’t stay dead long, duh, but it’s interesting to explore how the idea of a Batman goes beyond Wayne, preparing us for a far future when history texts conflate him with Jay-Z.

28. Rob Davis: The Motherless Oven trilogy (SelfMadeHero)

Some of the best visual world-building you’ll see, though it does eventually get a bit stuck in semi-explaining its lore. But until the end: mystery, action, characters you think you’ve seen before until their full complexity is revealed by a can-opener.

29. Hiromu Arakawa: Fullmetal Alchemist (Viz)

If this isn’t the best action manga, it might be the best with an ending that exists and is comprehensible, even if it’s just “everyone fights.” The characterization remains consistently strong, again in large part simply because the conclusion comes in time. Endings! They’re nice to have!

30. John Lewis/Andrew Aydin/Nate Powell: March (Top Shelf)

Few Americans deserved a hagiography more than Lewis, with the first book, covering his earliest years, providing the greatest added value. The impact lessens as the narrative moves to well-documented events: the treatment is about as tasteful as you can make the bleeding skulls of protesters. You should probably still read this, and everyone under 18 should definitely read this.

31. Jim Woodring: Poochytown (Fantagraphics)

Of the handful of Frank books I’ve read, this does the best at making the surreal-cute seem nightmarish-as-fjuck—there’s no distraction from romantic subplots, just psyched-out weirdness. Like early animation basically.

32. Haruichi Furudate: Haikyuu! (Viz)

One of the best of the “no, he’s like, really good at sports” shonen manga titles publishers push endlessly, perhaps because from the very beginning it’s about relationships, and the core ones continue to develop even as we meet every fjucking high school volleyball player in Miyagi Prefecture.

33. Ronald Wimberly: Prince of Cats (Vertigo/Image)

Ersatz Shakespeare is the best, and ersatz Shakespeare set in ’80s New York that draws from samurai movies and anime and No More Heroes is nearly the best ersatz Shakespeare. Read it before the Spike Lee movie comes out.

34. Matt Fraction/David Aja/Matt Hollingsworth: Hawkeye (Marvel)

Minor Avengers as agents of gentrification, with Pizza Dog the breakout superhero of the early 2010s and Hawkeye and Hawkeye’s teacher-student relationship not entirely unproblematic yet still very adult, which doesn’t mean grown-up.

35. Blutch: Peplum (New York Review Comics, trans. Edward Gauvin)

Roman pleb falls in love with an ice woman, then falls Caesar, pleb goes nuts, stabbings accelerate. Blutch’s blacks and whites (the protagonist sure seems to hang out in caves a lot) are extremely expressive, the scratches rendering anything remotely round as beautiful. For anyone who thinks that the veneer of civilization barely disguising a deep-seated tendency toward violence is something new.

36. Brian K. Vaughan/Fionna Staples: Saga (Image)

Probably the best character art of any Big Two-and-a-Half comic of the era. The creative team can make you feel the horror of violence as few can, though there might be more enjoyable things they could be doing.

37. Tetsu Kariya & Akira Hanasaki: Oishinbo: A La Carte (Viz, trans. Tetsuichiro Miyaki)

Cherry-pickings from Japan’s most successful manga for adults, which ran for thirty years before getting canned for questioning post-Fukushima food safety. The izakaya volume is my fave, which reflects my culinary preferences as well as the absence of the overarching anxiety-of-Tory-dad’s-influence storyline. Instead you see major life problems solved through the correct choice of regional cuisine and some of the most delectable food art since the 17th Century Netherlands, which has its downside if you’re 2,000 miles from a first-rate guts-on-a-stick joint.

38. Gipi: Land of the Sons (Fantagraphics, trans. Jamie Richards)

This post-apocalyptic survival/coming-of-age thingie is about FAMILY and LITERACY and all that, but more importantly it’s just good storytelling, with brutality and heartbreak and a shady dude in a diving mask who knows how to read. Very strong character art, getting at the humanity of people so far removed from civilization that one wears a “Hotel California” t-shirt and no one calls him on it.

39. Mira Jacob: Good Talk (Random House)

A “graphic memoir” that pastes flat, expressive character art and text over photos. Pretty moving, with the “how do you bring up a mixed race kid when your in-laws support Trump” theme obviously topical, while the “my strait-laced teacher who never got my name right drove to a drycleaner and an Elks Lodge and it was the most inspirational moment of my youth” story less obviously so, but no less valuable.

40. Alan Moore & Kevin O’Neill: League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century (Top Shelf)

Let’s just put all of the twentieth century in there and make the best Moore of this century, says me who can’t remember anything that happened in Promethea. The Sixties were honestly pretty good, but we’ll never have too many indictments of them.