At the beginning of the year I decided I hadn’t read enough comics in translation from languages other than Japanese. So I read… a lot of manga, honestly, but a reasonable amount of comics in French and a few other languages. A decent chunk was in the International Art Film style that’s stultifying the American graphic novel (families! sometimes they don’t get on!) but I found plenty I liked. What follows is in no way a comprehensive list: for many of the entries below, I’ve only dipped deep enough to know how much more I have to get to. Some obvious choices are omitted—you probably don’t need me to tell you to read Persepolis, but if you do, read Persepolis. Manga fans will have to wait until year-end lists for my Sakamoto Days appreciation.

DAVID B.

You also probably don’t need me to tell you to read Epileptic, but you should read Epileptic. The most acclaimed French graphic novel of its era hasn’t exactly resulted in a rush to publish his whole oeuvre in English, or to even to keep his Wikipedia page updated. The second book of Incidents in the Night, his next best known work, ends with a to-be-continued, and I can’t tell if there’s another volume that remains untranslated or if the story actually ends there. In a way, this is entirely appropriate for a series about esoteric books that may or may not exist. But in another more accurate way, it’s annoying, not least because the ideas of worlds within books and secret magical letters seem on the verge of becoming coherent.

Less frustrating is The Armed Garden and Other Stories: two tales of horny medieval prophets who kind of had a point, plus one about a drum made out of human skin, also horny. Thematically and visually, this is the most likable I’ve found him. Conflicts are represented by falling swords and jagged letters, with the strongest force the threat of the restoration of Edenian sexuality—good luck sealing all that into a well once it gets out. Much more minor is Nocturnal Conspiracies: just some dreams he had in his youth, illustrated in his trademark solid black and white.

LEWIS TRONDHEIM

France’s top fantasy cartoonist, and, like David B., a member of publishing house/clique L’Association. His magnum opus is the sprawling Dungeon series, which he writes with Joann Sfar and has been illustrated by seemingly every French cartoonist. The epic comprises a number of subseries with an arcane numbering system (issues go from -10,000 to 10,003); most of it isn’t available in English. I’ve only read a little of the Monstres sequence of side stories, since they’re ostensibly stand-alone works. Tales and artists flash by in fifty pages, not really enough time to get a feel for how the world works. Maybe in a few dozen volumes’ time it’ll make sense.

Much easier to digest is Ralph Azham, written and drawn by Trondheim while Sfar was busy making a Gainsbourg biopic. Blue duck-guy Ralph was supposed to be the Chosen One, except his power turned out to be an uncanny ability to know how many children someone has. This does eventually turn out to be useful, but it’s just one of the skills he has to rely on when it turn out he has to save the world after all. Trondheim’s an excellent plotter, keeping things moving at a breakneck pace as fatalities accumulate and hands get bloodied. Similarly the art crams a lot into small panels through facial (including beak) expression and Brigitte Findakly’s shifting colors. The translation of the fourth and final volume is due later this year—see, cartoonists, you can finish things!

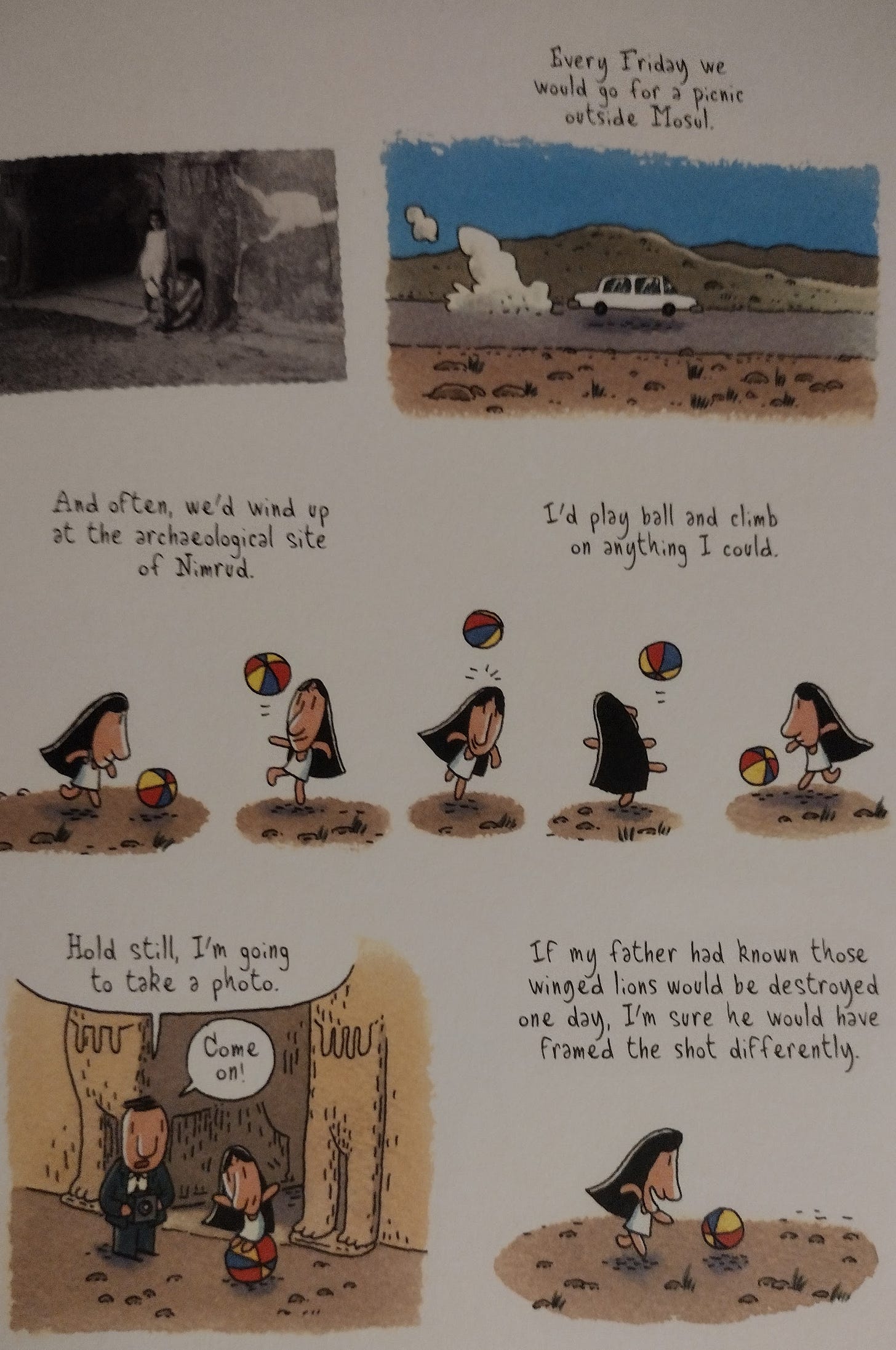

Charming and very much against type is Poppies of Iraq, created with Findakly (his wife.) The book contains episodic recollections of her childhood in Mosul and relevant incidents from her life in Paris. Trondheim brings a light cartooning style appropriate for the material; history supplies the weight.

EMMANUEL GUIBERT

Guibert has created several popular children’s series; what I’ve seen of those isn’t of much interest to grown-ups. More compelling to oldsters are his nonfiction works. Alan’s War is a memoir recounting the pretty ordinary WW2 service of GI Alan Cope—it’s February 1945 by the time he gets to Europe, where he blows up one (1) farmhouse; the greatest danger is getting run over by your own army. Perhaps the most interesting aspect is how people in his life drift in and out of contact with him (he dies in 1999; a shame, since he would’ve been good at Facebook.) Not strictly essential, but a pleasant read.

The Photographer was a decent-sized hit (as far as graphic nonfiction in translation goes) in 2009. The photographer in question is Didier Lefèvre, who accompanied a Doctors Without Borders mission to Afghanistan in 1986. The story is told through a mix of Lefèvre’s photos and Guibert’s drawings. The latter seem almost superfluous at first, Lefèvre’s vast empty landscapes and portraits of mujahideen on break and civilians injured by events that may or may not have anything to do with war are so evocative. Then Lefèvre decides to walk back to Pakistan without his MSF team. His trek becomes a struggle for life, and Guibert does a fine job of depicting the progression of his desperation. Still, even when things are hopeless, Lefèvre recovers his faculties for long enough to take out his camera: “to let people know where I died.” It’s a beautiful place.

MARCELO D’SALETE

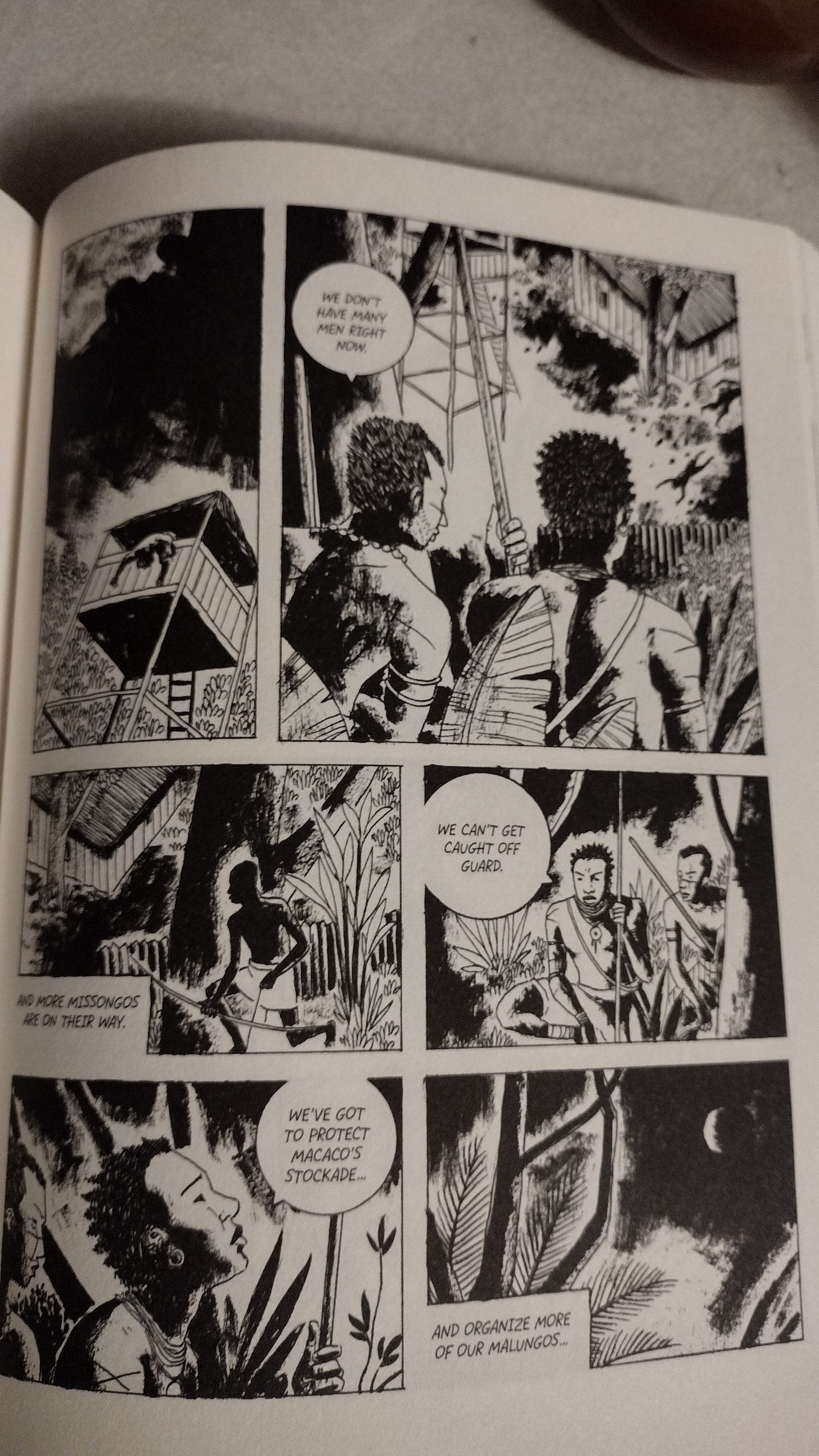

D’Salate has become Brazil’s most internationally acclaimed comics creator for his books about his nation’s history of slavery and the resistance to it. Run for It comprises four tales that don’t idealize the actions rebel slaves were driven to: desperate people do desperate things, and it’s not always the guilty who are harmed. (As usual, women get the worst of it.) Even in the cases where vengeance is attained, it has an incomplete feeling—past harms can’t be undone, which doesn’t mean you shouldn’t burn shit down. D’Salate’s sense of lighting and camera movements intensify the drama without drawing too much attention to themselves.

Angola Janga: Kingdom of Runaway Slaves is a big fat graphic novel about Palmares, the community of ex-slaves in northeastern Brazil in the 17th century, and its wars with the colonial authorities. This is much more narratively ambitious than the short stories in Run for It, and it doesn’t solve all the problems the source material presents (not least the “how do you prevent this from getting super-depressing at some point” problem.) Still, amidst the violence, there are enough minor victories and dynamic poses for the work to be inspirational for some.

MARGUERITE ABOUET

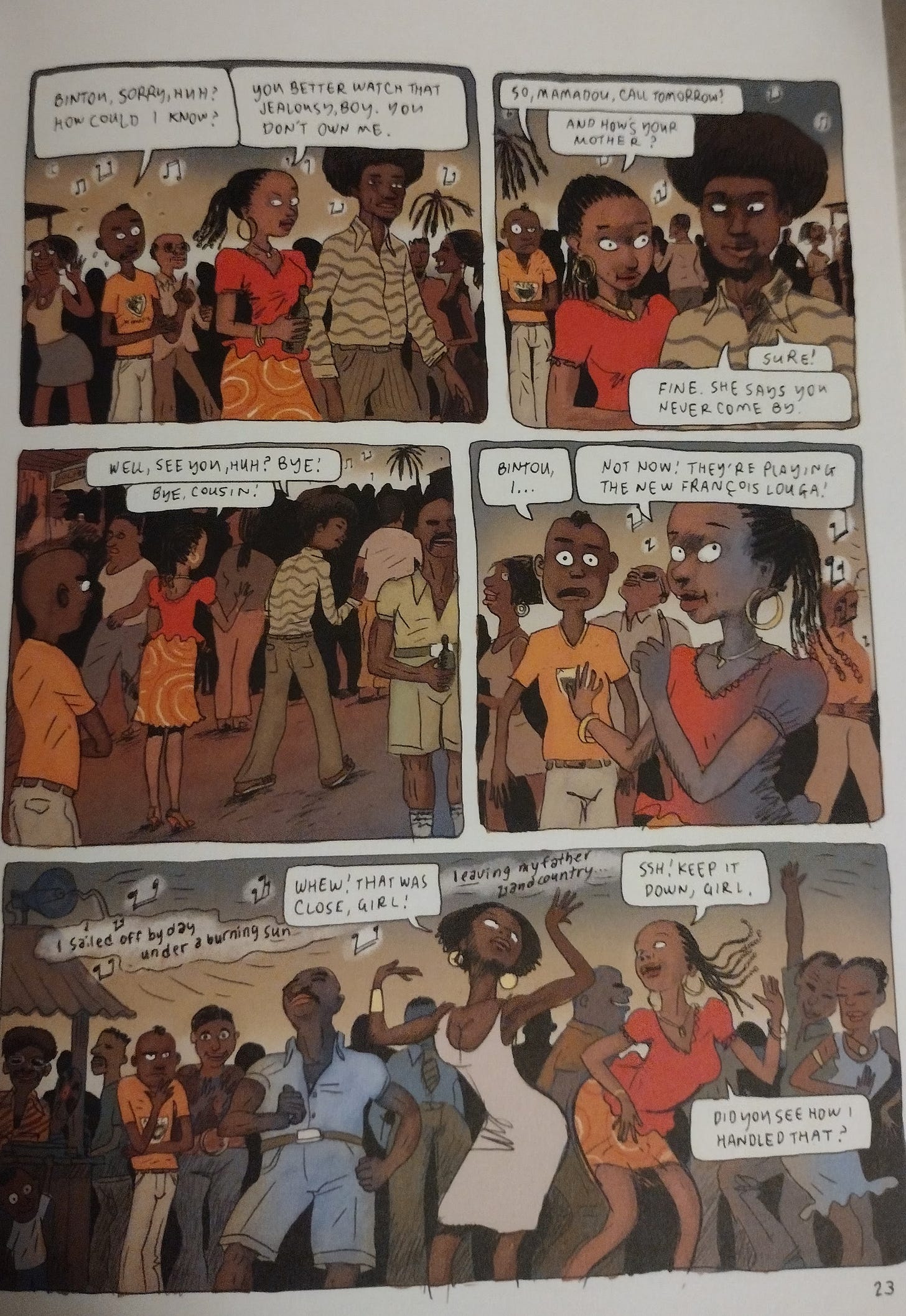

Abouet rose to comics fame with the Aya series, created with her then-husband Clément Oubrerie, between 2005 and 2010; the six books are available in English in the collections Aya: Life in Yop City and Aya: Love in Yop City. The stories follow the eventful everyday lives of teenagers Aya, Adjoua, and Bintou, and their network of family, acquaintances, and suitors, starting during the Ivory Coast’s 1970s boom. The extremely efficient graphic storytelling—each scene lasts a few pages and shunts the plot along without anybody appearing to be in a hurry—perhaps mimics the apparent pace of life in the era. As the affairs and unplanned pregnancies accumulate, characters decamp to Paris or the countryside, the vibe shifts from disco to Alpha Blondy, women and a nation grow up.

Abouet then wrote the children’s strip Akissi, drawn by Mathieu Sapin, about a Yopougon elementary schooler and her friends, with plenty of fart jokes. The setting makes it of some value to adults, if only because you can read it extremely quickly. A seventh volume of Aya came out in French in 2022; the English translation is due next year.

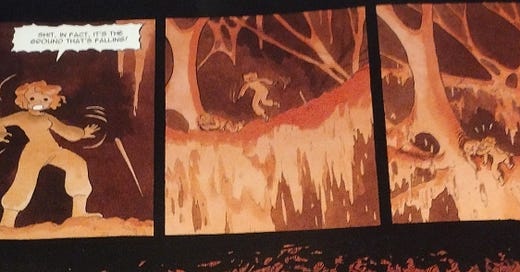

FABIEN VEHLMANN & KERASCOËT

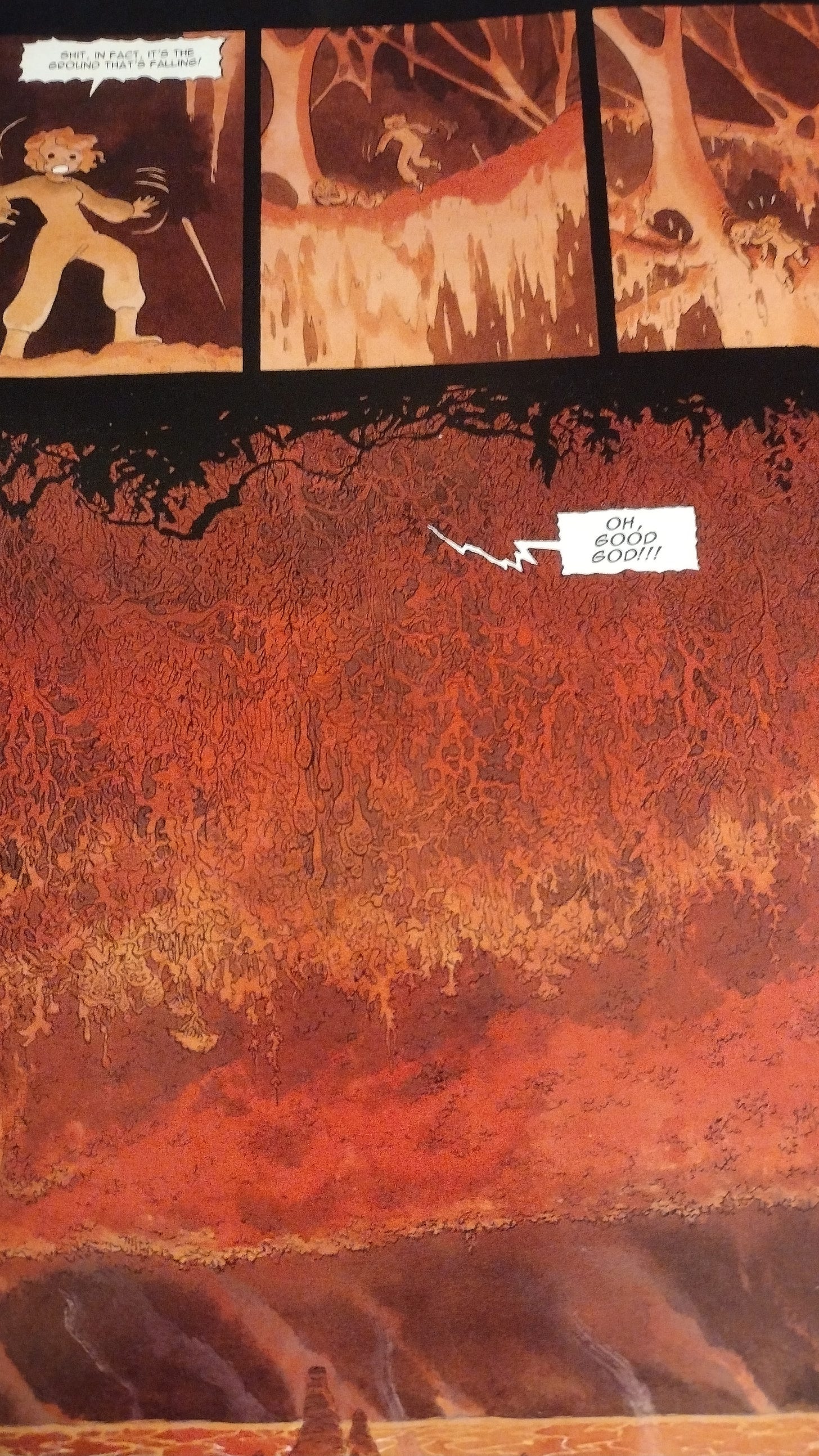

Vehlmann and Kerascoët (the latter the joint pseudonym for artists Marie Pommepuy and Sébastien Cosset) first collaborated on Beautiful Darkness. The story is slight (what if fairies were prone to homicide and enraged eye-gouging, but in a cute way), but writing and art match up very well. Satania is a fuller work, with Kerascoët going ham on a more varied bestiary, and Vehlmann getting some decent philosophical shots in amidst a stronger plot structure (plucky adventurers, one nubile, travel towards the center of the Earth and try not to die.) Separately, Vehlmann has taken over as writer of the Spirou & Fantasio series—Tintin’s less problematic rival, as I understand it—while Kerascoët illustrated Malala’s children’s book, which seems an odd fit given how much murder is in their books that I’ve read, but the Nobel Peace Prize seems to change people.

SUBJECT FOR FURTHER RESEARCH: PEETERS & SCHUITEN

A critic and philosopher, Benoît Peeters has written biographies of both Hergé and Derrida. He and Belgian artist François Schuiten are creators of the series The Obscure Cities. The only volume I’ve read is The Leaning Girl, which takes a non-realist premise (there’s a girl; she leans, unsupported, all the time) and works through it systematically. You could draw connections to the work of Peeters’s graduate advisor Barthes; I mostly looked at the pictures, which are outstanding. Schuiten’s compositions are inspired by the large format newspaper Sundays of the Hearst era but not in thrall to them, with the character art in particular bringing a contemporary edge to the chiaroscuro. I should definitely read more of the series, though not the biographies. Maybe one of the biographies.

Nice write-up. I'd propose adding Sfar's The Rabbi's Cat, which is a lovely intro to French Algeria, and has a pretty decent cartoon version.